Key points

- A book by an Episcopal priest explores the life of his great-great-grandfather, a Methodist clergyman and abolitionist.

- The Rev. George Richardson was chaplain for a Black Army regiment during the Civil War.

- George Richardson’s adventures are balanced by the Rev. James Richardson’s account of his own journey leaving a journalism career to become an Episcopal priest.

The axiom that history is written by the victors doesn’t hold when it comes to the story of abolitionists in the United States.

“The Confederates wrote a history that abolitionists were radical lunatics and that nobody really wanted to free the slaves except a few fanatics, and that the North really wasn't fighting to end slavery,” said the Rev. James D. Richardson, author of a new book that attempts to correct these errors.

“… It was a very deliberate way of rewriting history to justify what was really a treasonous war against the United States. Only in recent years are we coming to grips with that … and finally, really writing the history that needs to have been written all along,” he added.

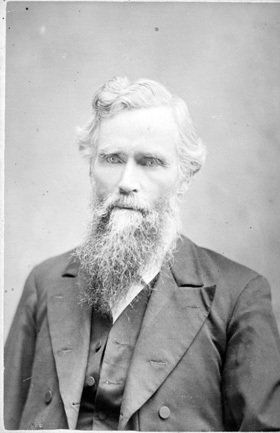

In “The Abolitionist’s Journal: Memories of an American Antislavery Family,” Richardson, a journalist and Episcopal priest, focuses on the story of the Rev. George Richardson, his great-great-grandfather. Written with the help of George Richardson’s unpublished memoir, it’s a harrowing tale of a Methodist pastor and abolitionist who risked his life for the cause of ending slavery.

George Richardson helped at least one slave — and probably more — to escape via the underground railroad, was chaplain for a Black Army regiment during the Civil War and once hid for 10 days in thick Texas woods from a murderous white posse angered by his support for Black people.

The pages of George Richardson’s “Recollections of My Lifework” contain “stories of war, white vigilantes, Black schools, church politics and frontier congregations,” James Richardson said in his book. “He recounted getting lost on horseback in Minnesota in the winter and the crushing devastation in the Mississippi countryside in the days after the Civil War. He wrote of life in Black shantytowns, Texas panhandle cowboys and Idaho Mormons.”

George Richardson’s cinema-worthy adventures are balanced by James Richardson’s account of his own journey leaving a thriving journalism career to take up his call to ministry. He worked at The Sacramento Bee, The Riverside Press-Enterprise and The San Diego Union covering politics, the Ku Klux Klan, the environment and other issues.

“I'm hoping by my telling my story that it has the effect of pulling the story forward,” James Richardson said. “I also feel like my calling as a priest and as a journalist are very related. … To me, both vocations are about bringing light into darkness and pursuing truth and afflicting the comfortable and comforting the afflicted.”

Author Neil Henry, the former dean of the University of California-Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, is the author of “Pearl’s Secret,” which traces his family’s mixed African American and white heritage. James Richardson said Henry’s book influenced the structure of “The Abolitionist’s Journal,” which also balances present-day autobiography and historic stories of ancestors.

Henry characterizes James Richardson as “a man of the world.”

“But he's also got a deeply spiritual side that was reflected in his book,” Henry added.

In addition to George Richardson’s memoir, James Richardson culled through other family journals and letters in his extensive research for “The Abolitionist’s Journal.” The Richardson family has a long tradition of putting their stories on paper, but its history with the abolitionist cause had been downplayed by his grandparents, James Richardson said.

“As we're all climbing the white social ladder, having this ancestor who worked with ‘colored people’ was a little socially awkward for them,” James Richardson said. “The larger story of the white social caste system had the effect of really making this something of an embarrassment in our family.”

James Richardson’s father didn’t feel that way, and mentioned his grandfather’s memoirs in his own unpublished autobiography.

“He made sure that my sister and I knew about the civil rights movement, watched the Selma … protests and the hideous reaction of the police in that community in the early 1960s,” James Richardson said. “He put us in front of the TV to make sure we saw it. He told me he admonished his mother to stop using the N-word.”

Richardson identifies strongly with his great-great-grandfather.

“I was kind of panicking about going off to seminary and quitting my (journalism) career and trying to figure out how to beg for my job back,” he recalled. “When I read (my ancestors’ memoirs), it kind of clicked in me that I'm joining the family cause here.”

Although there are parallels, he’s quick to acknowledge that he’s not the equal of George Richardson.

“I would not pretend to be George Richardson,” he said. “I've never put my life on the line like he did. I was never a chaplain in the Army. I have never had vigilantes trying to kill me.

“So, I'm not him.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.