In 1939, the Methodist Church told blacks they were not welcome in the same church pews as whites.

The Central Jurisdiction was formed as a racial compromise. African-American United Methodists from across the country gathered Aug. 27-29 to remember, reflect, and redirect their efforts regarding the history, problems and circumstances of the forced separation.

The Central Jurisdiction was established in 1939 and eliminated by action of the 1968 General Conference. Many Methodists — Dorothy Height, James Lawson, and Joseph and Evelyn Lowery, among others — were leaders for social justice on the national level and within their church. Blacks in the Methodist Church could not be part of the struggle for desegregation in society and not fight for the same reform within the church.

“The Central Jurisdiction was a compromise,” said William McClain, a professor at Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington, who was ordained in the Central Alabama Conference in the Central Jurisdiction. “It was a way that the church avoided integration. It was a compromise to bring the southern Methodist Church and the northern Methodist Church together and to merge them in 1939. The truth was that black people were abused, insulted and disappointed that the church was not willing to be one church.”

While Methodism’s founder, John Wesley, vehemently opposed slavery, racism was woven into the heart of American Methodism. It was an issue as early as the Christmas Conference in Baltimore in 1784, and ultimately the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions led to a church split in 1844.

Evelyn G. Lowery, convener of the reunion, welcomes participants. A UMNS photo by Mike DuBose.

When the separation happened, most of the African Americans protested and some left the Methodist Church. Others stayed, still seeking to live as God would have them, despite a church that would not.

More than 300 participants gathered for the reunion, with the theme, “Reviewing Yesterday, Discerning Paths to Tomorrow.” Evelyn Gibson Lowery, a United Methodist who founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Women’s Organizational Movement for Equality Now, conceived and organized the reunion. Her father, the Rev. Harry Gibson, served under the Central Jurisdiction.

Lowery and the Rev. Chester Jones, top staff executive of the United Methodist Commission on Religion and Race, led the event.

“The Central Jurisdiction Reunion is the first of what is hoped to be many to come since the merger,” Lowery said. “This reunion is long overdue, and we are hoping that it will be the beginning of efforts to educate persons about the past experiences of African Americans in the church.”

The participants shared stories of the former Methodist Church during segregation, and they drew comparisons between U.S. and Methodist race relations. Some noted that the nation moved faster than the church in dismantling racist structures.

“The Central Jurisdiction did not end officially until 1968,” said the Rev. Gilbert H. Caldwell, “whereas our U.S. Supreme Court had said that separate but equal was invalid in a 1954 Supreme Court Decision.”

From 1960 to 1966, W. Astor Kirk and James S. Thomas were part of a five-member committee commissioned by Central Jurisdiction church leaders to search for an inclusive Methodist fellowship. They were involved in a major reform movement aimed at purging the church of organizational structures based on race alone.

United Methodist Bishop Woodie W. White (right) and Barbara Thompson help lead a panel discussion during the Central Jurisdiction reunion. A UMNS photo by Mike DuBose

Kirk, in his book, Desegregation of The Methodist Church Polity: Reform Movements That Ended Racial Segregation, explained that the Committee of Five not only did a noble job for the Central Jurisdiction and the Methodist church as a whole, but it was committed that the Central Jurisdiction die with dignity and in a way that would be possible for the church to go forward.

Central Jurisdiction members recalled that although the segregation was painful, they made the best of a bad situation. For example, individuals had opportunities for leadership and growth that would not have been possible otherwise.

“I looked at (the Central Jurisdiction) as maybe a hindrance or a handicap at that time,” said Mai Gray, a retired educator. “But as I have thought of it more deeply, I have seen it as an opportunity.

“If we had not had a Central Jurisdiction,” she continued, “a lot of our people would not have had opportunities for real leadership, and so this to me, was a place where they learned and honed their skills. Even though it was not pleasant, it was still an opportunity.”

“When reunion finally became a reality in 1968, I knew the beneficiaries of this new church would not just be African Americans in the Central Jurisdiction,” said retired Bishop Forrest C. Stith, “but whites as well, for we brought with us not only a property or resource gain, but we brought a deep spirit of faithfulness and the love from one another that could not be transcended.”

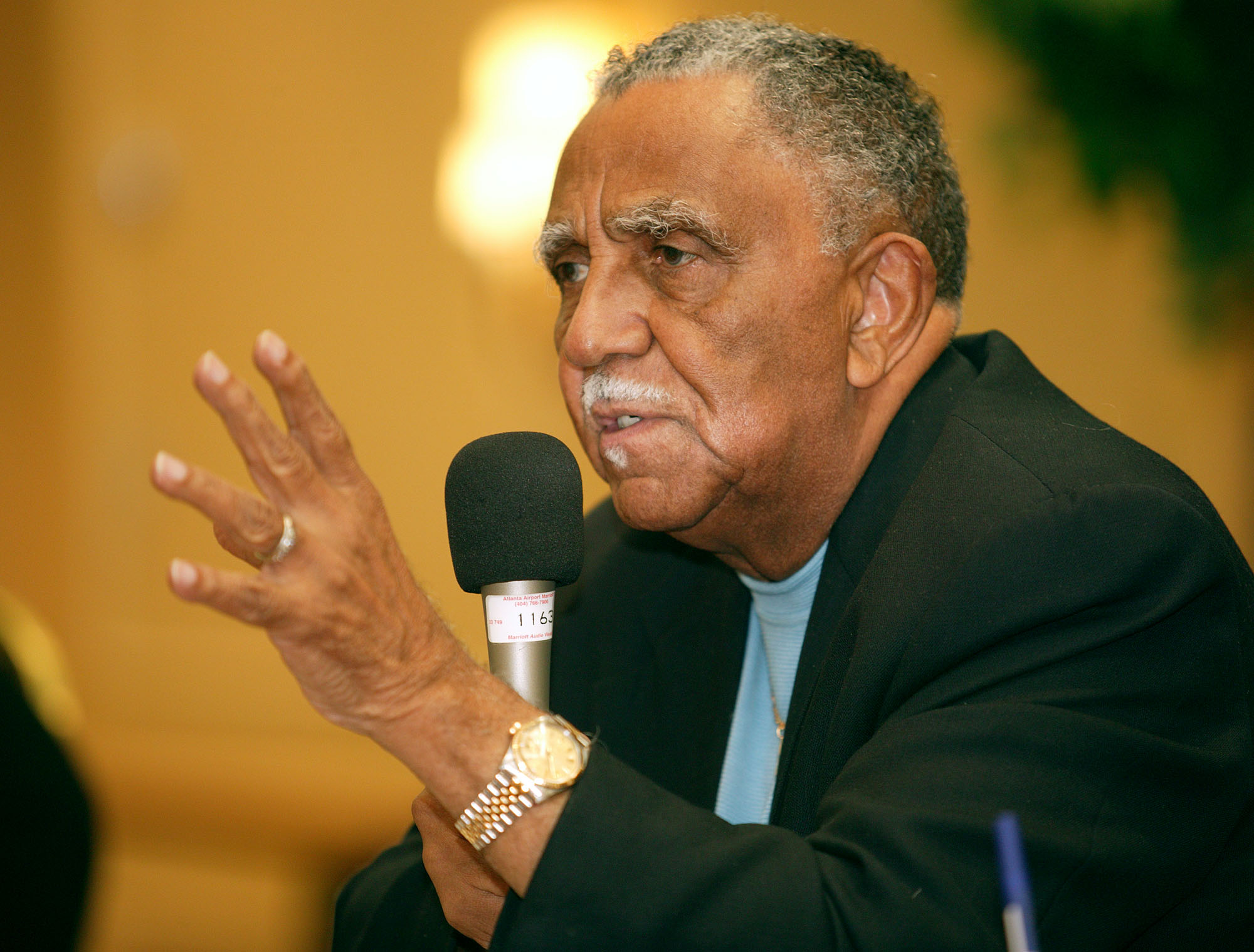

The Rev. Joseph E. Lowery helps lead a panel discussion during the Central Jurisdiction reunion. A UMNS photo by Mike DuBose.

Panel discussions covered the “Committee of Five’s Search for an Inclusive Church,” “The Journey: Telling the Story” and an “Evaluation of the Merger: Lost and Gained,” which included Bishop Woodie White, Joseph E. Lowery and Barbara Ricks Thompson. Lowery led the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; White and Thompson are former top staff executives of the United Methodist Commission on Religion and Race.

In a discussion of the future, speakers called for vision and action from all church members, examined the implications of cross-racial appointments, and challenged participants to become activists by “not only remembering history, but making history remember us.”

The final evening included a recognition banquet, honoring people from the 17 Central Jurisdiction conferences. After a service Sunday morning, the reunion closed with a fellowship picnic at Cedar Grove United Methodist Church.

Yvonne Williams Boyd, a pastor from Altadena (Calif.) United Methodist Church, said she was impressed by the event and the church’s rich history. She suggested having another Central Jurisdiction reunion for young adults, college-age students and new members “so we can reinforce the story, empower them to know their history, and support their work in the church.”

Today, more than 420,000 African Americans are members of the United Methodist Church in the United States, representing about 6 percent of the total U.S. membership. The Central Jurisdiction legacy continues 36 years later as the United Methodist Church seeks to revitalize black churches, provides relevant resources and holds special worship services to repent of its racism.

Editor's Note: This story was first published Sept. 1, 2004.

*Crosby is a freelance writer, video producer and consultant in Nashville, Tenn.

News media contact: Kathy L. Gilbert, Nashville, Tenn., (615) 742-5470 [email protected].

Related Resources

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.