Key Points:

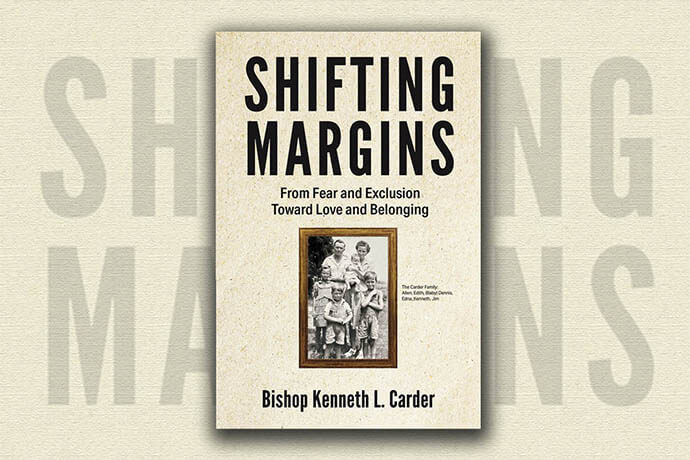

- The memoir “Shifting Margins: From Fear and Exclusion Toward Love and Belonging” finds retired Bishop Kenneth Carder wrestling with his own success.

- At 4 years old, Carder was nearly drowned by a drunken landlord, which later taught him an early lesson in power dynamics in society.

- He noted that his experiences have made him more comfortable with mystery than he is with concrete answers and certainties.

- The church offers the hope of real community in our increasingly fragmented society, Carder believes.

The memoir of retired Bishop Kenneth Carder is surprisingly joyful, considering it prominently features prison, dementia and the near murder of the author as a child.

Carder, 83, recalls his remarkable rise from childhood poverty to the sometimes uncomfortable halls of power in “Shifting Margins: From Fear and Exclusion Toward Love and Belonging.”

Going from church custodian to pastor to bishop to divinity school professor, Carder has often contended with imposter syndrome, a feeling of unworthiness despite his accomplishments.

“Those formative years as tenant farmers and being part of a fear-based, dogmatic, rigid religion had lifelong consequences,” Carder writes in the book. “It has not been easy to trust and love God. A deep sense of inferiority and of not measuring up dog me to this day.”

Carder, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, pastored in several churches before serving as a bishop in Tennessee and Mississippi. Two of his ministry focuses have been prisoners and people with dementia. The latter became a priority after his wife, Linda Carder, was afflicted with it. She died in 2019, but he has continued that work.

The following interview was edited for brevity and meaning.

You had a harrowing near-drowning experience at 4 years old, being held headfirst into a barrel of water by your family’s landlord. How did you process such a horrible memory?

It became a symbol of power differentiation. Now obviously, (children) are not thinking that way. But as I look back and note the dynamics between my dad and (the landlord), for example, and then how somehow that began to relate to my image of church or to my image of God. That’s where it has had a significant impact over the years, this God who is the dominant one who judges, punishes and demands respect. So, it was a dramatic experience that in retrospect over the years had also theological implications.

A theme that runs through the book is the friction between your modest roots and your success as an adult. Did writing the book help with your uneasiness with success?

Yes, it did. As I shared in the book, I hid from my poverty or I hid it from congregations and others. I was embarrassed. It seems silly now, but we’re still discriminating against and there’s this stigma attached to being poor. We all struggle with different kinds of poverty and privilege. Every privilege is accompanied by a blind spot.

That’s one reason we need community and that’s another thing I hope I captured in the book, the importance of relationships. I’ve been changed by relationships with those on the margins, some my own family. … My first Black friend was when I was in seminary. These same divisions are separating us today, the economic disparities in our country, the class divisions, elitism, race. There is rigid religion, anti-science, anti-reason and anti-intellectualism. They’re all still with us. I was hoping that perhaps my story and my journey in those arenas might be helpful to others.

Your roots are in a fundamentalist Baptist church, and as a child you switched to Methodism by making a deal with your parents that you could pick the church as long as you attended somewhere. Would you tell me about that?

I was 11 years old before I went to the Methodist Church. (Before that) it was an independent Baptist church. They didn’t call it fundamentalism, but that’s what it was. It was a rigid interpretation of Scripture, literal interpretation. There was not the application of the academic tools of looking at contexts and critical thinking. I did have that in college. … It’s a struggle we’re experiencing now, that religion is rigid and focuses on answers more than questions. That doesn’t value mystery as much as certainty.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

One of the motivations behind the book was to try to illustrate from my own story that discipleship is a continuing process of expanding the lens through which we view the world and life. It’s a continuous process of expanding the margins of our thinking, our perceptions and our relationships. Moving out of the provincialism of my childhood into a community where we’re all included, and a growing of comfort with and appreciation for mystery. I’m much more comfortable with mystery than I am with concrete dogmatic answers and certainties.

It was reinforced with me as a pastor in Oak Ridge (Tennessee, home to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory), at a church made up of predominantly scientists and engineers. We don’t have the final answer on anything, and every answer is accompanied by new questions. That’s true in biology. It’s true in chemistry. I think it’s also true in theology, that your insights raise new questions, and new questions lead to greater insights.

But aren’t people interested in religion looking for things like the Ten Commandments, the right rules to follow so everything will be OK?

Yes, I think many of us come to religion looking for final answers. But life tends to dislodge the final answers and open up new questions. That doesn’t mean that we have no convictions. I don’t see convictions the same as certainties. The bedrock commandment is the one Jesus left with his disciples: “Love one another as I have loved you.” Now that’s a bedrock conviction.

Are there ways your early poverty has been a blessing?

I think it gave me a deeper empathy for people who live on the margins, and perhaps it gave me a sense of indebtedness to others. It certainly sensitized me and gave me greater appreciation and understanding of the theological perspective that God is especially present with and among the least of these — the poor, the vulnerable, the imprisoned, the powerless. …

It also gave me a real sense of the importance of community. We are bound together and we help each other. One of the regrets that I have is that our communities tend to be more fragmented. We develop communities among the wealthy and the poor develop their own communities.

Can that tendency be overcome?

I think that’s precisely where the church comes in. The church is uniquely positioned, but we tend to divide in the same ways. That’s one of the reasons for all the current divisions within our denomination — progressive, traditional. I don’t like labels for people. But we need one another and it’s only together that we can even be who we are as children of God.

But the church has become polarized too, hasn’t it?

I think we’re following the culture. More than we’re being agents of transformation of the culture, we’re following the polarization of the culture. But also there is within our churches this tension between an emphasis on love and an emphasis on truth, as though those are separate dynamics. They are not separate. Truth is embodied. It’s incarnate. It’s not abstract theory. …

We need doctrines. They are part of the way we form our worldview. But to use doctrines as ways of deciding who’s in and who’s out, it seems to me is an abuse of the role of doctrine. We can believe that all people are made in the image of God intellectually without treating people as though they are made in the image of God. Authentic discipleship involves treating people with inherent worth and dignity, not simply intellectually affirming that they have inherent worth and dignity. So truth is to be practiced in love.

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.