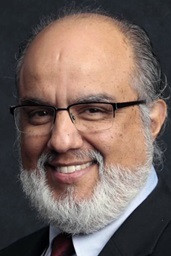

The Rev. Paul T. Stallsworth.

Photo by Krystal Baker.

Photo by Krystal Baker.

For years, the possibility of formally dividing The United Methodist Church has been discussed and debated, and now a proposal for separation to end the current church struggle will go to the next General Conference.

The discourse has always focused on how denominational division would affect United Methodists, but such a division would also influence society — actually, societies — beyond United Methodism.

The term kulturkampf, or “culture war,” was invented in the 1870s to describe the fight between Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s government and the Roman Catholic Church over the state’s attempt at cultural dominance in Germany. More than a century later, sociologist James Davison Hunter popularized the phrase “culture war” in the United States, applying it to the political conflict between conservatives and liberals, or traditionalists and progressives, on matters related to abortion, homosexuality, race and other controversial public issues.

Culture wars are now all over American public life. Whenever presidential politics, COVID-19 response, race/racism, abortion, homosexuality and gun rights are mentioned, most Americans quickly fall into opposing camps, with very few in the middle. The divide between conservatives and liberals appears everywhere — in politics, science, medical care, education, higher education, entertainment, denominational life and even the local church. The divided United Methodist Church lives and moves and has its being in a very divided society, and similar divisions seem to be unfolding in other countries as well.

Commentaries

UM News publishes various commentaries about issues in the denomination. The opinion pieces reflect a variety of viewpoints and are the opinions of the writers, not the UM News staff.

Noll said that U.S. churches played an active role in civil society for decades leading up to the Civil War. He stated that the Bible, understood authoritatively, led evangelicals not only to personal faith but also to public witness and work.

In his book “The Civil War as a Theological Crisis,” Noll said that as the slavery issue heated up across the nation, evangelicals on both sides — abolitionists in the North and pro-slavery advocates in the South — used the Bible to make their own cases.

Therefore, Noll said, evangelical Protestants “who believed the Bible was true and who trusted their own interpretations of Scripture above all religious authorities constituted the nation’s most influential cultural force. By 1860, religion had reached a higher point of public influence than at any other time in American history.”

Despite this public influence, the evangelicals (including a large proportion of Methodists), relying on their individual interpretations of the Bible, could not settle the issue of slavery. Contention spilled into the culture and then into the political realm, leading to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.

Tragically, because Methodists themselves were divided — and eventually split in 1844 over slavery — they could not help the nation resolve its crisis.

Richard John Neuhaus (1936-2009), the Lutheran pastor and later Roman Catholic priest who was committed to the church’s witness in the public square, often asserted: “Culture is the root of politics, and religion is the root of culture.”

Mindful of that idea, what can we say about the witness of a divided church in a divided society?

When a divided church cannot make up its mind about its own faith and life, societal division often aggravates division in the church. Methodism struggled with slavery in the 1800s and with sexuality over the last 50+ years. In both cases, the church’s lack of biblical and traditional doctrine and discipline made it vulnerable to the divisive culture wars and political battles of the day. When a divided church formally separates in such circumstances, it looks distressingly similar to other institutions that are unraveling in the polarized society.

When a church considers dividing, authority in that church is diminished. Its doctrine, morals and discipline likely become matters of choice for its clergy and laity. That is what happened in American Methodism in the 1800s, and that is what is happening in American Methodism in our time.

When a church divides, the culture and politics of the resulting denominations can become extremely, irredeemably predictable and partisan, with no space for people with different cultural commitments and different political views to gather. Post-division denominations tend to provide religious refuge for society’s conservative and progressive tribes. Such churches cannot, with integrity, challenge the extreme polarization of culture and politics in the larger society, since the churches are themselves polarized. At their worst, such churches usually allow polarized people and institutions to grow even more entrenched in their partisanship.

When a church remains unified and carries catholicity in a polarized society — even if those practices are far from perfect — that church’s witness can be powerful. That church, secure in its identity as the Body of Christ, confident in living under the Headship of Christ, can be a strong sign of contradiction (Luke 2:34) to a divided world.

It can invite all, from the left and the right, to repent and be baptized. It can welcome all to the Lord’s Table and it can offer the preaching and teaching of the Word of God to all. It can become a gathering place for all, in Christ’s name, to call into question the idolatries of the world’s politics. It can become Christ’s countercultural community that demonstrates a different way, a faithful way, to live in a divided world.

“Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.” — I Corinthians 13:4-7 (NRSV)

Stallsworth is the editor of Lifewatch, the newsletter of the Task Force of United Methodists on Abortion and Sexuality. A longer version of this article appeared in the December newsletter.

News media contact: Tim Tanton or Joey Butler at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.