Crowds jammed into the Tennessee state capitol on a hot August morning in 1920 for what all expected to be a momentous day.

The question on everyone’s mind: How would the Tennessee legislators vote on U.S. women’s right to vote?

Ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution required 36 states’ approval, and 35 states were already in hand. However, ratification was far from assured.

Most of Tennessee’s southern neighbors had rejected the measure. The state’s legislature faced pressure to do the same and begin sounding the amendment’s death knell.

Suffragists in the gallery that morning knew that only 47 of the 96 legislators present were committed to their cause. They had little hope that eastern Tennessee Rep. Harry T. Burn, the state’s youngest legislator at age 24, would join their ranks.

The suffragists could see that Burn’s lapel bore a red rose, a symbol of opposition to the women’s vote. What they could not see was the letter in his pocket — carrying advice from his Methodist mother.

“Dear Son: Hurrah, and vote for suffrage!” Phoebe "Febb" Burn wrote from the town of Niota, Tennessee, where she attended what is now Niota United Methodist Church. “Don’t keep them in doubt.”

Her son's sudden “aye” tied the vote and emboldened fellow legislator Banks Turner to give the decisive 49th assent. Thus, Tennessee secured women citizens a voice in their nation’s democracy, including in that year’s presidential election.

A more perfect union

United Methodist Women also has plans to bring a resolution urging “Voting Rights Protections in the U.S.” to the coming General Conference, now set for Aug. 29-Sept. 7, 2021, in Minneapolis.

People across the United States today are marking the centennial of that historic vote on Aug. 18, 1920. However, achieving this victory took more than one mother’s letter, and the fight for ballot access continues even now.

“The right to vote is the one expression of our shared civic life which has the ability to level the playing field in real time and for the future,” said the Rev. Sharon Austin, director of connectional and justice ministries with the Florida Conference. Austin is working for the voting rights of the formerly incarcerated.

She can attest that women weren’t given the right to vote. They took it and won many male allies along the way.

The 19th Amendment followed more than 70 years of persistence through setbacks and sacrifice. The people called Methodist were part of the struggle from almost the beginning.

“Methodists have a long history of strong, leading women,” writes the Rev. Susan Lyn Moudry, a historian, in an article for the United Methodist Commission on the Status and Role of Women.

John Wesley accepted women lay preachers and class leaders from his movement’s earliest days.

So it’s perhaps no surprise that the first Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, found a welcoming host in the Wesleyan Chapel, part of the Wesleyan Methodist denomination. Historians typically identify the 1848 gathering as the start of the organized women’s suffrage movement.

Back then, advocates for women’s rights and the abolition of slavery worked closely together. Sojourner Truth, a former slave who began her public ministry as an itinerant Methodist preacher, was an activist for both causes.

But after the U.S. Civil War, opponents to change successfully drove a wedge between the activists. The 15th Amendment assured only African American men had the right to vote, and even that assurance soon proved weak in the face of states’ Jim Crow laws.

Meanwhile, many white suffragists turned their backs on the struggle for racial equality to focus on fighting for their own access to the ballot box. While women could vote in a handful of western states, starting with Wyoming in 1869, their success at the national level remained stubbornly elusive and multiple state referendums on the women’s vote went down to defeat.

Into this fray came the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Under the leadership of Methodist Frances Willard, the group sought to do more than encourage abstention from alcohol. The union fought to improve working conditions in factories, institute an eight-hour workday, raise the age of consent for girls and secure for women the right to vote.

“Many Methodist women, like Frances Willard, saw the vote as a way to further their aims,” said Harriett Jane Olson, United Methodist Women’s top executive. “It was not just a right. It was a necessary tool.”

However, Olson acknowledged, many Methodist women also counted among the opposition.

Take it to the ballot box

“Because the right to vote did not extend to all women, it is appropriate to adopt what others have said, we ‘commemorate’ rather than ‘celebrate’ the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment,” she said.

The first step is to register to vote. The National Association of Secretaries of State has a way to check if you are registered to vote.

The word suffrage comes from the Latin word suffragium, meaning voting tablet. Still, opponents were happy to play on its similarity to another English word. With women’s suffrage, critics argued, men and families would suffer.

Willard did not live to see the 19th Amendment’s ratification. Neither did her fellow women’s rights’ activist, the Rev. Anna Howard Shaw.

Shaw, one of the first women ordained in the Methodist Protestant Church, was president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association for 11 years. She served as a bridge between the Seneca Falls generation and younger suffragists who would go on to advocate for equal rights in all aspects of American life.

However, Shaw and her fellow suffragists were often deeply divided on the best tactics to pursue and perhaps most profoundly on matters of race.

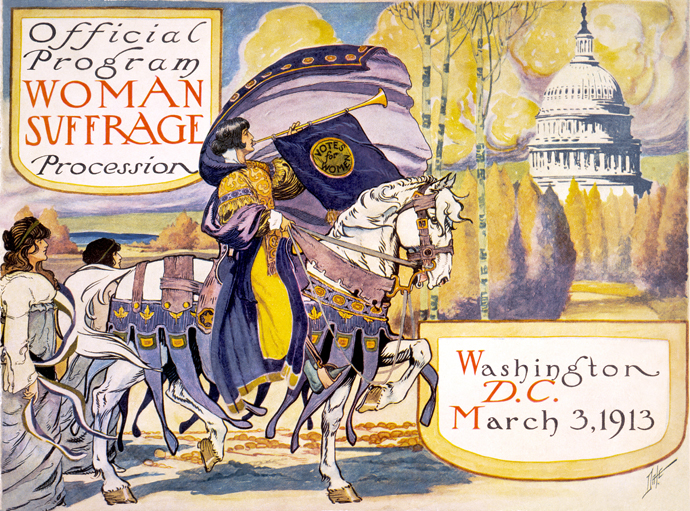

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, baptized a Methodist while a student at Rust College in Holly Springs, Mississippi, was a pioneering Black journalist, anti-lynching activist and suffragist. However, fellow suffragists asked Wells-Barnett — one of the most seasoned veterans in the fight — not to walk alongside them during the landmark 1913 national suffrage parade in Washington. The women’s suffrage association feared alienating white support.

But when a mob overtook the parade route and began beating women marchers, Wells-Barnett rejoined her fellow suffragists in the chaos.

“One had better die fighting against injustice than die like a dog or a rat in a trap,” was Wells-Barnett’s motto.

That was not the only violence suffragists would endure on the road to ratification. They continued to face mob attacks and when arrested for civil disobedience, they endured brutality in prison — including force-feedings when they went on hunger strike.

“We don’t need to sugarcoat that it was all these pretty women in white dresses with yellow sashes. They sacrificed,” said Annette Dorris, who serves with United Methodist Women in Tennessee’s Cumberland River District.

She and other United Methodist Women in the district are using the 19th Amendment’s centennial as an opportunity to encourage U.S. citizens to vote, especially in Tennessee. In 2016, Tennessee ranked 48th in the nation for voter turnout among all states and the District of Columbia.

“Let’s honor their sacrifice by getting out and voting,” Dorris said.

Dorris also sees in Febb Burn’s timely letter the difference one mother can make.

Immediately after her son's surprise vote for suffrage, the young legislator faced heated accusations that his vote was bought with bribery. In a moment of personal privilege, he responded.

“I want to state that I changed my vote in favor of ratification first because I believe in full suffrage as a right; I believe we had a moral and legal right to ratify; and I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow,” Harry Burn said.

Burn's vote, important as it was, did not accomplish full suffrage. Many Black, Native American, Hispanic and Asian American women who had struggled for the 19th Amendment's passage still were denied access to the ballot box. Methodist women such as Mary McLeod Bethune, Jessie Daniel Ames and Dorothy Height would continue the fight for voting rights and racial justice long after that August day in 1920.

Moudry, the United Methodist historian, said the Methodist involvement in the women’s suffrage movement shows that change is long and hard.

“The work for justice does not happen overnight; we cannot get discouraged or give into moments of defeat,” said Moudry, who is also the coordinator of clergy and lay leadership excellence in the Western Pennsylvania Conference.

“Leaders are needed who build bridges and help the church understand the issues involved in justice work,” she added. “This takes great courage and unwavering commitment, even in the midst of seemingly insurmountable obstacles.”

Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.