Key points:

- In 1952, DeLaris Johnson Risher and Leila Robinson Dabbs, both Black women, quietly integrated Scarritt College for Christian Workers in Nashville, Tennessee — two years before segregation in education was ruled unconstitutional.

- The official naming of The Johnson Robinson House on the Scarritt Bennett Center campus in Nashville honored both women April 2.

- Risher looks back on those days and her long career, which includes being the first Black Methodist deaconess.

DeLaris Johnson Risher doesn’t look, act or talk like a trailblazing, fearless woman — but she is.

In 1952, she and Leila Robinson Dabbs, both Black women, quietly integrated Scarritt College for Christian Workers in Nashville, Tennessee, two years before segregation in education was ruled unconstitutional. Dabbs died in 2002; Risher is 92.

The official naming of the Johnson Robinson House on the now Scarritt Bennett Center campus in Nashville honored both women April 2 and kicked off a yearlong campaign called “It’s Always a Time for Radical Change” to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the college.

Risher led the ribbon-cutting along with Dabbs’ relatives.

At the time the women entered the college, segregation was being heavily enforced to the extent that not just imprisonment, but the lynching of African Americans had occurred in Tennessee only a decade before, according to research done by the Scarritt Bennett Center.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

The Ku Klux Klan had a public office just a few streets away from Scarritt in what is now Nashville’s famed Music Row.

“It has been a wonderful opportunity to research the storied history of the college and continue to discover all its golden treasures. These two women, who dared to stand up for women of color 70 years ago, richly blessed the history of this institution,” said the Rev. Sondrea Tolbert, executive director of Scarritt Bennett Center.

Risher, a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc., was also honored at a reception of the Nashville chapters of the sorority on March 31.

“DeLaris is strong and confident, yet gentle in spirit, with a delightful sense of humor,” said Celinda J. Hughes, co-chair of the reception sponsored by the Nashville Metropolitan Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc. “Sitting and talking with her was like being at her kitchen table with a gracious lady and lifelong friend.”

During the reception, Risher talked about how she came to Nashville and shared story after story about her long career, which includes being the first Black Methodist deaconess.

“My minister, the Rev. Isaiah DeQuincey Newman, recommended me when the United Methodists decided they would integrate Scarritt,” she said. Newman was a civil rights activist, United Methodist pastor and later a state senator of South Carolina.

Risher had a degree from South Carolina State College in social studies. When she started at Scarritt, she majored in sociology.

She chose her major, which she calls social group work, because “I wanted to help people.” Her first field assignment was to the Bethlehem Centers of Nashville, a United Methodist-related center for children, youth and seniors in North Nashville.

Students from the area came to the center after school, she said, “and I was supposed to keep them active until their parents arrived. I played ‘Ring Around the Roses’ and all the games I knew.”

However, she said, “I found out social group work was not for me. I’m an educator!”

Though Scarritt did not have all the courses necessary for her to change fields, nearby Peabody College did. Students at Scarritt could attend Peabody and Vanderbilt, but those schools had not yet approved of integration. Officials got together and decided they would admit Risher.

Her first day at Peabody was in a conference room with just the professor. “They did not permit me to go to the classroom,” she said. “I went back and told my professors at Scarritt, and the next course I took, the professor told me which classroom to come to.”

Smiling, she remembers that at the end of that first class, all the students rushed up to her, saying, “Oh, we are so glad you are here. Thank you, thank you.”

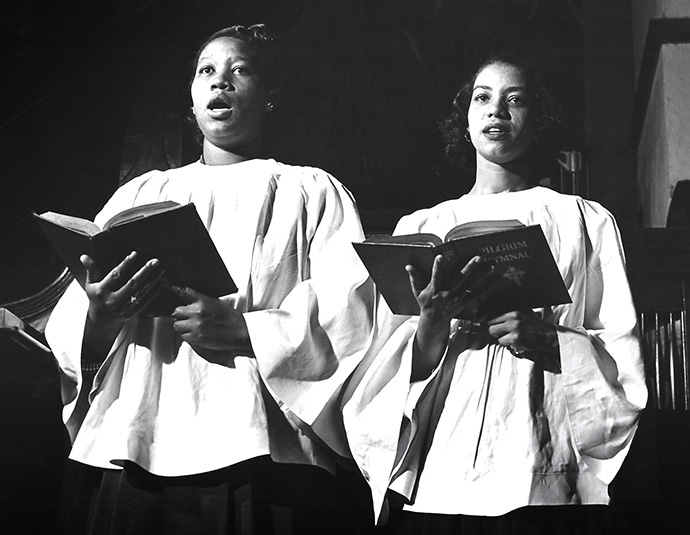

Photo courtesy of Scarritt Bennett Center.

“I had no more trouble at Peabody. They accepted me and the same at Vanderbilt,” she said.

She did have a bit of trouble when she and a group of girls from Scarritt wanted to go to the Grand Ole Opry.

“We were lined up in front of the ticket office and the ticket man looked at us — well, he was looking at me — and asked, ‘Where are you gals from?’

“One of the girls told him we were from Scarritt. He said, ‘Wait here, I’ll be right back.’ He brought the manager back. The manager looked at us and said, ‘Let those gals in. That Black girl might be an African princess and I don’t want any trouble with an African princess.’”

She became a licensed Methodist deaconess in 1955 and her first assignment was to the Navajo New Mexico Conference in Farmington, New Mexico, as a teacher for Native American children.

Leila Robinson Dabbs’ legacy

After graduating from Scarritt College with a master’s degree, Leila Robinson Dabbs worked for 30 years at Sager Brown School in Baldwin, Louisiana, at Bethlehem Center in Fort Worth, Texas, and later in Johnson City, Tenn., as a deaconess for the Holston United Methodist Conference. She was president of the Central Jurisdiction Deaconess Association for 15 years. She died March 9, 2002, at the age of 72.

She spoke lovingly of that appointment.

Her first class was a group of Navajo children who did not speak English. “They came in all bashful, looking around, looking at me.” Navajo high school students were assigned to serve as her interpreters.

“When I got my high school students, we had fun,” she said. She wrote a story for the 1962 World Outlook, “Along the Navajo Trail,” about her work.

When her parent’s health started failing she got a job at Claflin University, a historically Black United Methodist college in her hometown of Orangeburg, South Carolina. She met her husband, Modie L. Risher Sr., there and they married in 1959. She retired after 35 years of teaching.

Risher said her two years at Scarritt were “wonderful.” She said she was not afraid to be one of the first to integrate the school because she had been in so many integrated groups at home.

In her book “Yes, Lord, I’ll Do It!” Alice Cobb, a former Scarritt teacher and writer, wrote about those days when Johnson and Robinson came to the campus.

“Looking back, over a quarter of a century, all this does not seem very daring or innovative. In 1952, it was. … The really hard times for integration were to come a few years later, after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968.”

Risher smiles and brushes aside any comments about her bravery.

“I love this college and I appreciate all the teachers, professors, president, students,” she said. “So many just opened their arms to me. I enjoyed every day on this campus.”

Kathy L. Gilbert is a freelance writer in Nashville, Tenn.

News media contact: Julie Dwyer at [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Friday Digests.