Key points:

- The 2nd Chance Indiana ministry supports inmates as they prepare for life after release, helping them find places they can live and work successfully.

- The formation of 2nd Chance followed a serious accident that led United Methodists Jim and Nancy Cotterill to reevaluate their priorities.

- Many assumptions about felons are incorrect and helping them succeed improves society, they say.

A lot of what is assumed about prisoners after their release from prison is inaccurate, say a United Methodist couple who run the innovative 2nd Chance Indiana ministry.

Jim and Nancy Cotterill, part of the group that founded the Indianapolis Business Journal, established Unite Indy, the predecessor of 2nd Chance Indiana, in 2016. They have been helping prisoners to succeed upon their release since then, so they know their stuff.

Here are some of the things they’ve learned:

- Contrary to media portrayals, many times correctional institution workers, including wardens, genuinely want to help prisoners get ready to succeed on the outside or live some kind of reasonable life if they will never get out;

- Former convicts succeed in the workplace and are retained at about the same rate as non-convict hires;

- People who have served longer sentences because of the seriousness of their crimes succeed more often in the workplace than people who serve less time for comparatively lesser crimes;

- The No. 1 reason that former prisoners fail in the workplace is lack of consistent transportation;

- Many convicts can’t get a job because they can’t afford a place to live; and

- The menial-task jobs that convicts can usually get are a good place for them to start, because it can build confidence and it feels good to be part of a team.

All these insights and the whole 2nd Chance Indiana ministry stem from Jim’s tragic 2001 bicycle accident while vacationing on Mackinac Island in Michigan.

“I was out for a bike ride with my son in the evening, and I hit a little spot that I didn’t see and kind of went over a small cliff and ended up breaking my neck,” Jim Cotterill recalled.

After waking up in the hospital from a medically induced coma, he was paralyzed from the waist down. He needed a ventilator to breathe.

“They didn’t know if I’d have ever have use of my arms,” he said. “They were pretty sure that I wouldn’t walk again … . I had a lot of time to think and I had a lot of time to pray, and I got the idea that maybe God was (trying to tell me something).”

In time, Cotterill did regain the use of his arms, the ability to breathe on his own and walk, although he still puts up with tingling, itching and burning in his arms and hands. Surprisingly, the experience changed the couple’s lives in a good way, too.

Members of St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, the Cotterills became motivated to do more altruistic work.

“I think (God) used it in a big way to change our lives,” Jim Cotterill said.

Jim never lost his confidence in God, Nancy Cotterill added.

“When he was laying paralyzed, he said, ‘I know that I am supposed to get out of this bed and help people.’ He didn’t really know what at first, but we figured it out,” she said.

First, he founded the National Christian Foundation, which helps people raise money for charitable causes while avoiding capital gains taxes. Eventually, he moved on to helping prisoners succeed after their release.

Sharing testimony

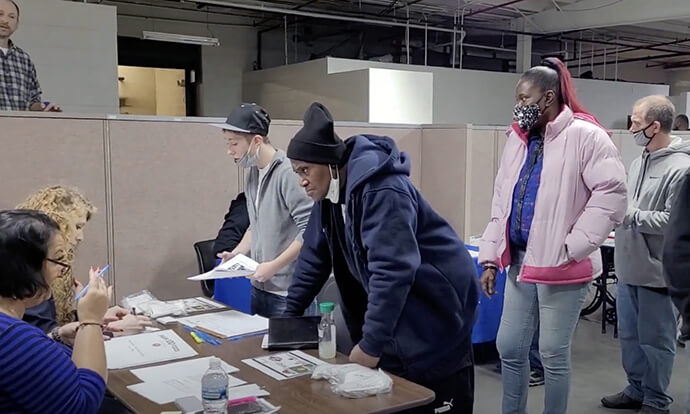

In videos posted by 2nd Chance Indiana, two clients offer their thoughts on how the program helped them transition out of prison into a successful life and career.

Today, 2nd Chance Indiana helps inmates prepare for the job market ahead of their release with the Jobs for Life course, offers a listing of jobs available to people with felony convictions and access to helpful service providers for things like mental health and addiction recovery, and provides mentoring.

There are many reasons former prisoners fail at life after getting out, and 2nd Chance Indiana helps them deal with most of those factors.

“If you come out of prison, you come out in an older body but you’re still a kid in terms of your growth level,” Jim Cotterill said. “You can go to work and act in an inappropriate way, whether it’s what you say or what you wear, or how you deal with people, that gets you fired immediately.”

The program begins while a felon is in prison but has a release date approaching.

“The first thing is not a job,” he said. “They need to be worked with before they get out so that they’re ready for a job.”

Training starts 20 to 270 days before a prisoner’s release date. They are taught the virtues of work, like using their God-given talents to support their family, and that work can be part of loving their neighbors.

There are more immediately practical things reviewed: how to write a résumé, how to speak in the interview.

“It’s basic job preparation training, but all undergirded with a foundation (of Christianity),” Cotterill said.

Each inmate in the program is assigned a mentor, a volunteer. There are three levels of mentor, starting with correspondence only to frequent meetings in person, depending on the mentor’s comfort level.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“We assign a (volunteer) to you that either comes in and goes through that training with you or weekly touches base via video kiosk that they have in some of the prisons and jails, or the visitor comes (into the prison),” he said. “They can talk over the course, and the whole point is they start developing a relationship.”

The mentor can help identify obstacles that might interfere with successful reentry to society, starting with where they’ll live once released.

If the family isn’t open to welcoming the ex-prisoner back, many think they can “couch surf” with old friends. That is usually a bad idea.

“Are those the people you were hanging out with when you got in trouble? Nope, don’t go there,” Jim Cotterill said. “We want you in a safe place, so maybe we'll find a faith-based place we can put them in that we know it’d be safe for him, that kind of thing.”

Holding a job is often as hard for ex-convicts as getting one. Most of the jobs are menial labor or factory work, and transportation is usually an issue if a car isn’t affordable. 2nd Chance Indiana has 16 vans it uses to get ex-convicts to work and back, and some factories offer their own transportation.

It’s important to teach pride in their work, no matter what it is, Cotterill said.

“Let’s say it’s sweeping floors — and I hate to sweep floors,” he said. “What I say to him is, ‘Be the best floor sweeper that they’ve ever had. … Let them see you scrubbing that floor like nobody’s ever scrubbed it before, and they’re going to say, ‘We want that guy to move up.’”

Clients also get help developing a personal career path, including a career assessment test and plan of action.

Nancy Cotterill said that all the training and mentorship comes down to offering love to someone who needs it.

“What we’re doing is infusing love into them,” she said. “These people often have a very empty love bank. … We’re going to find out what you’re good at, because you need to be happy when you work. You need to pursue something that you’re good at, because we all have our own talents. That’s probably real news to them.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.