Reported incidents of sexual harassment within The United Methodist Church have decreased in recent years, according to the results of a denominational survey released Jan. 30.

The one exception in the summary of “Sexual Misconduct in The United Methodist Church: U.S. Report” was for seminary students, where reported incidents increased. The 2017 survey by the United Methodist Commission on the Status and Role of Women follows surveys the commission conducted in 1990 and 2005.

As the report’s introduction noted, participation in the 2017 survey concluded before allegations against film producer Harvey Weinstein and others snowballed into the #MeToo movement that concentrated public attention on how women are treated in the workplace and in society.

Survey snapshot

- Clergy, laity and church employees experienced fewer incidents of sexual misconduct since 2005.

- Seminary students reporting incidents of misconduct jumped from 51.3 to 68.4 percent.

- Women are more at risk than men and clergy more than laity.

- Perpetrators of sexual harassment and misconduct are more likely a local church member, colleague or seminary student.

- Knowledge about church policies on sexual misconduct has declined across the board.

Find more at Women by the Numbers on the commission’s website or read the entire report.

That public focus “is making us more vigilant in recognizing and being aware and reporting in the church,” said East Ohio Area Bishop Tracy S. Malone, the commission’s president.

“It’s really about accountability and establishing a culture of no tolerance for it (sexual misconduct),” she explained. “That this is a safe place.”

The denomination’s Council of Bishops joined with the commission on Jan. 23 to issue a statement about the #MeToo movement, encouraging “the reporting of sexual misconduct, including sexual harassment allegations within the church.”

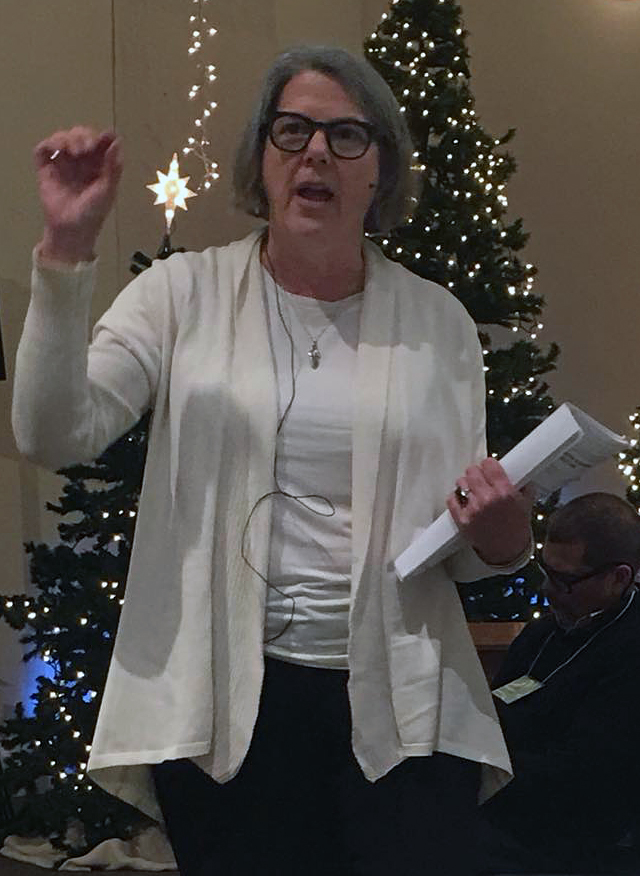

The week before the survey results were released, Becky Posey Williams, the commission’s senior director for sexual ethics and advocacy, was crisscrossing the denomination’s Rio Texas Conference as she led training sessions for some 500 clergy members.

The #MeToo movement has really opened the conversation, she said. “There’s this freedom to talk now.”

Williams already had received calls because the survey included her contact information. “Every one of those calls had to do with issues that a person had experienced and wanted to know more information about the process or what could be done now,” she said.

Perhaps the most surprising finding was a drop in awareness of denominational policies related to harassment and sexual misconduct that are already in place. “Knowledge about policies, where to report and agency services has declined for men and women, clergy and lay, and in many cases, the decline is quite large,” the report said.

Becky Williams, director for sexual ethics and advocacy for the United Methodist Commission on the Status and Role of Women, leads a Jan. 24 training for the denomination’s Rio Texas Conference at Manchaca United Methodist Church near Austin. Photo by the Rev. Teresa Gayle Welborn..

“It is clear that we need to continually reinforce to annual conferences, seminaries and agencies the need for making our sexual misconduct policies well known throughout the connection, as well as the procedures for reporting an incident,” said the Rev. Leigh Goodrich, senior director of education and leadership.

Dawn Wiggins Hare, the commission’s top executive, said the lack of resources for laity about sexual misconduct was evident when she assumed leadership. Training over the years has focused on clergy, bishops, seminarians and response teams, she said, adding, “you’ve got to tell folks in the pews what is and is not acceptable.” She also said pastors sometimes face harassment from members of their own congregations.

The Commission on the Status and Role of Women is in the process of developing a theologically grounded, four-part curriculum — called “the integrity project” for now — that is designed to foster open conversations about values among laypeople. It also will help them know when they are experiencing sexual harassment and provide information about what would constitute harassment of clergy members by laity.

More than 4,300 responded to the 2017 sexual misconduct survey, about two and a half times the rate in 2005, Goodrich said.

She attributed the increase to the use of technology, rather than paper copies, to distribute the survey to a more diverse sample of United Methodists. That diversity, she added, “should make the data more statistically valid and reliable.”

Although the number of reported incidents has declined, those who experience sexual misconduct still find it hard to handle, said the Rev. Gail Murphy-Geiss, a former commission president involved in the survey’s creation and data analysis.

Find Help, Start Conversations

When possible victims of sexual misconduct call the United Methodist Commission on the Status and Role of Women, Becky Posey Williams said she asks every one of them if they are aware of a policy within their church to identify and report such behavior. “Unanimously, to this day, the answer is no.”

That answer is borne out by the commission’s 2017 sexual misconduct survey, which shows that such knowledge has decreased across the church.

In response, annual conferences can expect to see materials to help spread information about policies and procedures from the commission this spring, said the Rev. Leigh Goodrich.

“Additionally, we encourage churches, seminaries and agencies to prominently post their sexual misconduct policies and reporting procedures on their websites, in their offices, and in restrooms with a phone number for contacting their local response team member or other church leadership,” she said.

People can also directly contact the Commission on the Status and Role of Women at 1-800-523-8390. The United Methodist sexual ethics website also offers information and a variety of resources.

The denomination’s Social Principles, which reject that one gender is superior to another, is a longtime resource and a “wonderful way” of introducing the topic of sexual harassment, Williams suggested.

While the more serious incidents are likely to lead a person to a request a transfer or quit, “the most common response to any sexual misconduct is to avoid the person and ignore the behavior,” she said.

Because seminary students are younger than the average United Methodist, their responses indicating more experiences of sexual misconduct could show an awareness that this behavior is inappropriate, she said.

Murphy-Geiss hopes that every United Methodist becomes aware of appropriate and inappropriate language and behavior over the next decade.

So far, however, the task of building awareness falls to a Chicago-based denominational agency with a small staff, a limited budget and one person — Williams — who leads the training events.

The Commission on the Status and Role of Women used to be strictly a U.S.-centered agency, Hare explained. But as global representation on the commission’s board increased, “the need for this work and these resources around all of Methodism” became clear.

Part of a $300,000 grant from the denomination’s Connectional Table is being used for translating sexual harassment policies and related resources into the church’s other official languages, such as Portuguese.

“We can provide training,” said Malone, who developed a training plan for the Council of Bishops that Williams led in November. “We need to be more intentional about making it clear to clergy and laity how to access it.”

Training primarily occurs in annual conferences and local churches. But because of the findings about sexual misconduct in seminaries, the commission may need to be more intentional about inviting seminary staff to be a part of that, Malone said.

Prevention is possible, Williams believes, if church members accept that sexual misconduct is fueled by deeply rooted attitudes about power and gender. “I have to believe that we can do a better job than we have done,” she said. “But we’ve got to have the resources to do it.”

Bloom is the assistant news editor for United Methodist News Service and is based in New York.

Follow her at https://twitter.com/umcscribe or contact her at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.