I was born and raised in a small, two cotton-gin town in Louisiana. My parents, teachers and pastors rarely— if ever— mentioned the civil rights struggle.

Many of my neighbors probably were listening to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and experiencing the pains and struggles of growing up in what I would describe as a “tiny racist Southern town,” but I don’t remember ever hearing a word.

I lived on the “wrong” side of the railroad tracks, which meant most of the streets behind and beside our street were home to black families. I literally walked across the railroad tracks every morning and afternoon to attend the all-white school in town, while just a few steps from me was the all-black school. Both were public schools, but it wasn’t until my senior year in 1974 that the two schools were fully integrated.

My days were filled with being the oldest and only girl in my family, often charged with caring for my three younger brothers. Most of my free time was devoted to reading books from the town library. Those books did provide me with a glimpse into other worlds and I dreamed and prayed for a life beyond the edges of that small town.

In my role as news writer for United Methodist News Service, I have been privileged to meet some of the civil rights giants. In 2009, I walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., behind Rep. John Lewis and others in the 9th Congressional Civil Rights Pilgrimage organized annually by Faith and Politics Institute housed in the United Methodist Building in Washington.

I have sat in the pews and heard sermons from the Rev. Joseph Lowery and the Rev. James Lawson. I call Bishop Melvin G. Talbert a friend. I interviewed the late Dorothy Height for a special feature, Walking with King, produced by UMNS.

And so, God did answer my prayer for a life larger than the one I grew up in.

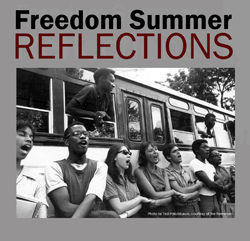

What was Freedom Summer?

In the summer of 1964, thousands of civil rights activists went to Mississippi and other Southern states to help African-Americans register to vote. At the time, only 6.7 percent of the African-Americans in the state were registered to vote, the lowest in the country. Most of the activists were young white college students from the North.

The Mississippi Freedom Party was formed and a slate of 68 delegates went to the national Democratic Party convention in Atlanta City to challenge the all-white Mississippi state delegates. The effort failed but drew national attention.

Freedom Schools were established to address racial inequalities in Mississippi’s education system.

Many suffered during that summer, three young volunteers were murdered, many churches and black homes and businesses were burned and many were beaten by white mobs or police.

However, Freedom Summer left a positive legacy. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed in part because the country had been educated by Freedom Summer.

I hope you will read these reflections and gain some insight into the real struggles of people following God’s direction. I invite you to send a reflection of your own to [email protected]. Please include a photograph of yourself and, if you have one, send a photo from Freedom Summer.

John Goodwin, United Methodist photographer, retired from the Board of Global Ministries

In the spring of 1963, I graduated from college. That August I was thrilled to participate in the March on Washington for jobs, peace, and freedom. The following April, I was drafted into the Army.

When the civil rights legislation was signed into law, I was still in basic training at Ft. Gordon, Georgia, and in a unique position. My barracks was roughly divided into three ethnic groups: Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and white Americans. I was a crossover person.

I spoke some Spanish, so I was accepted in the Puerto Rican group. My bunkmate was African American and he and I were a rarity in the group; we were both college graduates. Our friendship made me a de facto member of the African-American group and the color of my skin made my membership in the white group automatic.

When we heard of the signing (of Civil Rights Act) several members of the African-American community found a way to get some whiskey and held a sort of a celebration party to which I was a part. A racist-talking white young man from Virginia asked what was going on. When we told him the purpose of our celebration, he decided to celebrate too, if he could drink with us. He was welcomed to join in.

I was soon shipped off to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to radio repair school, so my only real involvement in Freedom Summer was that initial celebration, a meaningful time in an unlikely place.

The Rev. John W. Van Tine, retired ordained elder, Peninsula-Delaware Annual (regional) Conference

I had just graduated from high school in June 1964 and was working at Camp Fairlee Manor, an Easter Seal Camp near Chestertown, Maryland, in July 1964. Camp Fairlee Manor had been integrated since its beginnings in the 1950s. All people regardless of color were welcome to serve on its staff and to be “campers.”

“Campers” were those with physical or mental handicapping conditions. In the summer of 1964, our “head boy counselor” was African American. (He was soon to be promoted to assistant camp director.) We had other African Americans on staff.

I found it a great experience to work with all types of people. (I am Caucasian). My high school had integrated in 1963 and we had 26 African Americans in my graduating class of 192.

The Rev. Victor (Leon) Cyrus-Franklin, assistant pastor, Holman United Methodist Church, Los Angeles, California

Editor’s note: Franklin also took part in UMNS’s Walking With King

What comes to mind when I think of the Civil Rights Act of 1964? In a word: struggle, the struggle of generations to change policy in this country in order for us to live more fully into our espoused values of freedom, liberty and equality.

We take for granted the liberties the Civil Rights Act of ‘64 protects, but it was through multiracial coalitions of persons and organizations who worked for generations, even with internal contentiousness, to outlaw discrimination in this country.

Yet, it’s also a reminder that passing legislation does not change attitudes and behavior. Dr. King often reminded us that desegregation was a short-term goal, but integration, defined as “genuine intergroup and interpersonal doing” is the ultimate goal of our country. Learning how to struggle together across social lines to create a free and just community is hard work. The effort is fraught with passion, disappointment, forgiveness, enlightenment.

I think the 1964 CRA represents that. It’s an example and sign of how the struggle was worth it and that we are called to continue to live into that struggle to protect dignity, freedom and justice for all people, especially those persons and communities who through institutional polarization are pushed to the margins.

With the black freedom struggle as a driving force, the Act highlights the intersectionality of discriminations that touch all citizens of this country and is a bridge for many to factor in the need to preserve basic human rights for all people, citizens or not, if we are to truly be the “land of the free.”

Walter Kimbrough, president of Dillard University, New Orleans, one of the 11 historically black universities related to The United Methodist Church

I was born after the Civil Rights Act, so I am part of a generation that was not alive for most of the landmark civil rights decisions. The good thing is that we were born into a world where blacks could always vote in the United States, where we didn't have to take poll tests, or sit in segregated spaces.

But the bad news is that both Generation X and the Millennials often take the sacrifices of our elders for granted. We take the right to vote for granted, and if we don't connect with a candidate (as we did with President Obama) we quickly dismiss our role in voting. Many have adopted a slacktivist mindset where all of our protests are via Facebook posts or hashtags. I'm afraid we might be a generation of cowards, easily swayed from taking stances that might pose a serious risk, like losing a job or being expelled from school.

I hope we would never need to have such extreme levels of activism that were needed in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but if we did, I'm concerned that my generation and the ones that follow aren't up to the task.

The Rev. Phyllis Tyler, retired ordained elder, California Pacific Annual (regional) Conference

It was me, an 18-year-old freshman at Iowa's Morningside College, raised in the rural state of South Dakota, who found it a privilege to be housed at the home of Dr. Ethel Johnson, then Christian Education director at Bushwick Avenue United Methodist Church in Brooklyn.

She later was the first African-American professor at a United Methodist seminary in Ohio. My white, adopted upbringing by United Methodist parents had convinced me that the situation of disrespect to black people of the south was as wrong as the disrespect of the Sioux Indians in my home state of South Dakota. I was serving as a summer worker at the Brooklyn church along with 15 other white and black students for the summer.

My mission and passion as an adopted orphan and the teachings of the precious nature of all people by the Christian faith had generated what was to become a lifelong mission of my involvement in justice issues, with 40 years as a United Methodist clergy member. My Selma/Montgomery march with Dr. King was part of the birth of my passion for justice and respect. The summer of 1964 incubated my heart and soul for getting in "holy trouble" all my life.

The Rev. James H. Galloway, director of Missions & Congregational Care, Soapstone United Methodist Church, Raleigh, North Carolina

On June 10, 1964, the day the Senate voted cloture, assuring passage of the Civil Rights Act, I was under an oxygen tent with pneumonia, watching from my hospital bed. Although not quite 11 years old, I was an ardent, outspoken supporter. My dad, a physician, had a portable TV with rabbit ears placed on a table so I could watch the vote. Dad said, “This is an historic day that you will remember when you have grown up.”

Gilbert is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected].

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.