Key Points:

- Pastors serving in cross-cultural ministries gathered in Atlanta to offer each other support and strategies for navigating challenges.

- Complaints of bias and racism were aired, including that getting ordained is harder for non-whites.

- The United Methodist Church needs to continue to be pushed to address these issues, said the Rev. Giovanni Arroyo, top executive of the United Methodist Commission on Religion and Race.

Proud Americans in a predominantly white United Methodist church outside Atlanta fly an American flag to mark Veterans Day.

Who would object? You might be surprised to find out that such flag-flying could alarm non-white residents of the neighborhood. In the eyes of some, the American flag has been coopted by white supremacists and far-right groups as a symbol, clouding the waters for patriotic Americans.

“One of the ways that people of color identify a potentially racist scenario is when they see a church that is an all-white church and they're particularly passionate about the American flag,” said the Rev. Tony Phillips, associate pastor of Bethany United Methodist Church in Smyrna, Georgia.

Phillips, who is Black, has a calling to bring diversity to churches like Bethany where membership does not represent the multicultural communities in which they are set.

“It's gentle conversations,” he said. “You're looking at that flag and you're like, ‘Gosh, we shouldn't put that out there.’ But you can't remove it because it would cause so much friction (that) Fox News would be down there.”

Such issues pop up “left and right,” he added.

“There's a group going on a field trip and they're going to the ‘Gone With the Wind’ Museum,” he said. “Of course, that’s probably not something that people in our (non-white) community are going to embrace.”

Discussions like this abounded at the Facing the Future conference, held Nov. 14-16 in a downtown Atlanta hotel. The United Methodist Commission on Religion and Race event drew about 300 attendees, mostly United Methodist pastors serving in cross-cultural ministries. The goals of the conference included offering support and affirmation and providing practical workshops to help pastors in such ministries.

There were expressions of hurt and hope.

“This is the reality of cross-racial, cross-cultural ministry,” said the Rev. Giovanni Arroyo, top executive at Religion and Race. “One of the reasons why this conference came into existence is, ‘How do we create a place that contains space where this group of leaders across the church could actually be vulnerable, and not feel like this can be used against them?’”

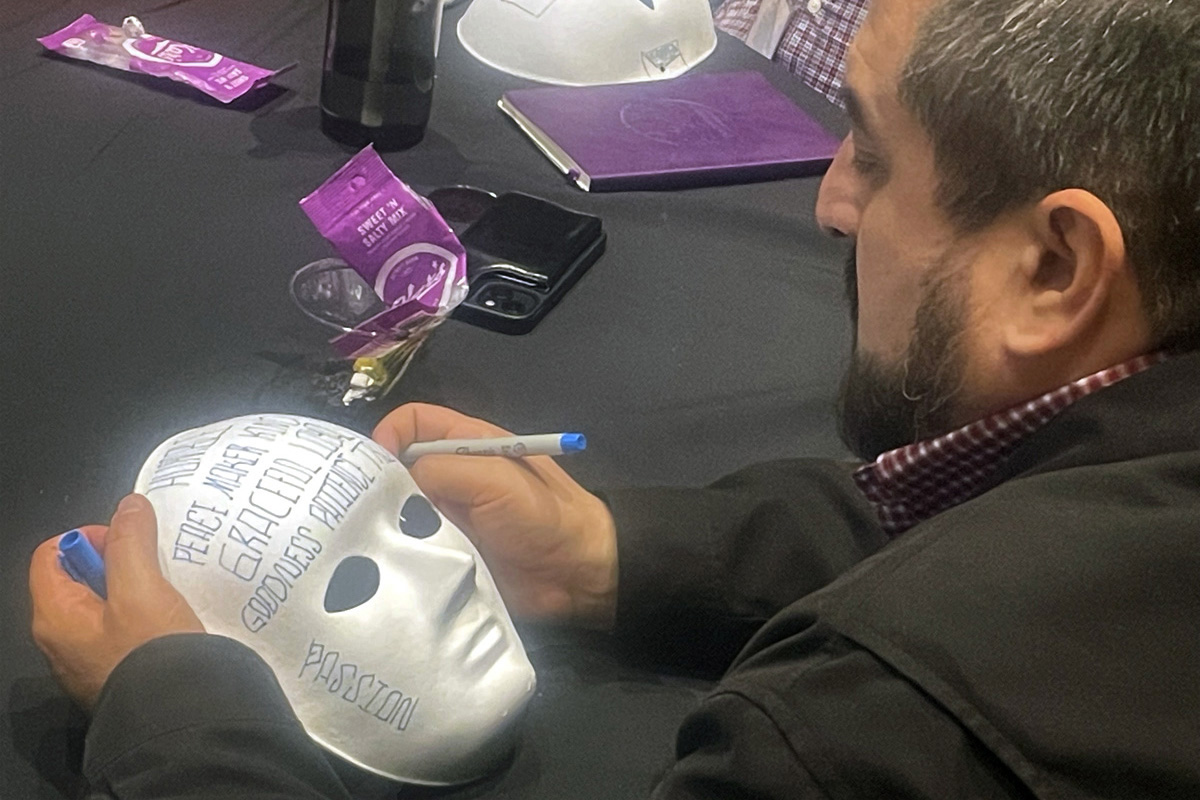

In a revealing exercise during the conference, blank masks were distributed to the pastors, who were invited to decorate them with colored markers. The outside of the mask was to express the face they show to the outside world, while the inner mask was to reflect how they wish others would perceive them.

“We may go in wearing a mask to do what God has called us to do, because we can't fully walk into who we are in our ethnicity,” said the Rev. Dyanne Corey, an elder in Virginia. “I want to be in a place where I am embraced for who I am and I can preach the way God birthed me to preach — and to feel the joy again of my call.”

Dawn Houser, pastor of Aitkin United Methodist Church in Aitkin, Minnesota, is a Native American leader at the majority white church.

Houser said her name and appearance give her the option to hide or downplay her Native American background, but she doesn’t do that.

“When I started the appointment there, they did not know that I was Native American,” Houser said. “They're a good group of folks,” she added. “It's interesting for them. I don't think they consider my appointment to be a cross-cultural appointment.”

Her heritage does make her approach to Christianity a little differently.

She prefers to preach about the story of Native Americans rather than that of the Israelites of the Old Testament, and she doesn’t refer to Jesus as “Lord.”

“To people who have been colonized, it's a real problem,” she said. “(Not using Lord) doesn't have anything to do with Jesus. (Native Americans) would take it as a slight toward Jesus.”

Houser reports receiving racist threats from people outside the church, including threats of violence.

Workshops at the conference included “Navigating Bias,” “How to Lead an Emotionally Intelligent Church” and “Empathy and Burnout.” The emphasis was on giving tools to pastors who are weary because of the hard circumstances of their jobs.

“I think the question (of the conference) is, ‘Are we trying to change people back home, or are we trying to create space for us to recognize and deal with our pain?’” Arroyo said.

“We have to recognize who we are and where we are,” he added. “Then it could be better able to navigate when we go back.”

Some pastors of color say they sense a racial component in their struggle to even get ordained.

“I've been in the board ministry ordination process for a long time,” said Eric Reniva, the Filipino and Puerto Rican pastor of Waterman United Methodist Church in Waterman, Illinois. “My biggest gripe is that you're good enough to lead a local church, but you're not good enough to be ordained.”

He said he has seen white pastors have a smooth journey through the ordination process and get plum appointments, especially legacy pastors — those with family members who have held positions of authority in The United Methodist Church.

But not him.

“There's always something wrong with your answers,” Reniva said. “You're not Wesleyan enough or you don't understand this or that or you don't have a great explanation for (the Book of) Discipline and polity.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“When they were talking about systems that hold you down and make you fearful, that's one of them for me.”

Arroyo says he has had similar feelings, despite rising to be a top church official.

“I think as a person of color, I know that I have to work harder than my siblings who are white, just so that I could be seen that I'm almost equal to the leadership — almost.”

Being vocal about racial issues doesn’t seem to be a good option, Reniva said.

“I've experienced it in seminary, and I've experienced it in my own personal ministry,” he said. “When you preach truth to power, you get stomped on. I mean, you may get punished for it.”

Not all the pastors at the conference are struggling. But the Rev. Grace Han, a Korean pastor at historically white Trinity United Methodist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, says some issues remain.

Han, the daughter of two United Methodist clergy, has noticed that nobody ever assumes she’s the pastor of the church. She has to tell them. And tricky discussions do come up.

“I was at my church when George Floyd was murdered, and in light of all of the Black Lives Matter movements, I've tried to have some really honest conversations about how we think about race, how we talk about race and how we address racism, especially when it's right on our (television) screens for everyone to see.”

She has begun having those conversations, but more are needed, she said.

“I don't want to paint it as like a perfect situation,” Han said. “I recognize that I've been blessed in my context, and I appreciate that and I value that.

“So there are success stories, and not just painful ones.”

Arroyo said that individuals and organizations like the Commission on Religion and Race “have to keep on pushing.”

“We are called to do better, so that we can move on to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which is love. I think that's important.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.