The helicopter swoops in lower, its big blades pounding, while fine pale dirt envelopes the U.S. Border Patrol agents as they turn and run headlong into tall sugar cane.

Agent Robert Rodriguez — parked at the crossroad — is listening to the chatter on the radio. All morning the Air and Marine Operation helicopter has been circling, helping the agents track a group of undocumented immigrants.

Rodriguez rolls down his window, slowing down when he spots footprints. He gets out to speak to the agents searching.

A radio call sends agents running toward a corner of the cane field, hoping to catch immigrants being flushed out of hiding.

Then he hears a distress call and runs back to the vehicle to grab bottles of icy cold water.

An agent drenched in sweat has started showing signs of heat distress. Suddenly the mission has changed from flushing out undocumented immigrants to helping a comrade.

Rodriguez gets the agent in his car and turns up the air conditioning. Soon two border EMTs are on the scene and more agents arrive, pouring out of their vehicles.

They give the overwhelmed agent hydrating solution mixed with cold water, get ice packs on his body, take his temperature and start monitoring his vital signs.

The agent has been running hard since 5 a.m. and even though he has been drinking water, it wasn’t enough in this punishing 100-degree Texas heat.

U.S. Border Patrol agents pour water over the head of a fellow agent who became overheated while searching a sugar cane field for a group of people who had entered the United States illegally. The high temperature for the day was 100 degrees.

Border patrol agents come to the aid of a fellow agent who became overheated while searching a sugar cane field for people who entered the U.S. illegally.

Moments later, one immigrant staggers out of the sugar cane field and surrenders to officers. He gets the same hydration solution and cold water and his condition is monitored.

The immigrant’s hands are shaking and his eyes are tearing. The agents don’t rush him, he is given time to recover. They find out he is 24, from Guatemala, and has been on a 10-day journey.

“A lot of people have misconceptions about border patrol, they think we are out here pounding people. We use appropriate force needed to apprehend people. When that kid came out of the sugarcane, we gave him our water,” Rodriguez says at the end of a four-hour ride-along with a reporter, photographer and a United Methodist pastor.

All in a day’s work.

A Guatemalan man who was caught hiding in a sugar cane field in 100-degree heat after crossing into the United States illegally drinks a hydration packet offered by border patrol agents.

The McAllen station is the busiest U.S. Customs and Border Protection station in the nation for apprehending undocumented immigrants and drugs. It is located in a rural Texas town where the winding Rio Grande narrowly divides the U.S. from Mexico.

Agents patrol 53 miles of the river, which is surrounded by farmland on the U.S. side and tall trees and thick underbrush in Mexico.

Driving the white-and-green border patrol vehicle along the levee, Rodriguez points to a small wooden structure perched among the trees on the Mexico side. “There is always someone in there watching. Looking for how many agents are out. People underestimate how organized these organizations are."

Rodriguez says there are two categories of people crossing the river — families looking for a better life in the U.S. and members of the Mexican cartel. “Fifty percent are people trying to get arrested and 50 percent are hiding and running.” If arrested, asylum seekers can ask for a safe harbor in the U.S.

U.S. Border Patrol Agent Robert Rodriguez (right foreground) removes handcuffs from a woman caught crossing the Rio Grande near McAllen.

What does the church say?

In its Social Principles, The United Methodist Church recognizes all people, regardless of country of origin, as members of the family of God and opposes policies that separate family members from each other.

Read more about immigration and the church

“First and foremost you never know who you are encountering, even people with families. We have had full-blown gang members coming in trying to skirt the system with little kids,” he says.

Rodriguez took the Rev. Robert Lopez, United Methodist El Valle and Coastal Bend District superintendent for the Rio Texas Conference, United Methodist News reporter Kathy L. Gilbert and photographer Mike DuBose for a ride-along.

As he was explaining the role of the border patrol, a call came in from agents who had captured two coyotes — men hired to smuggle immigrants across the border.

Two shirtless, heavily tattooed, men are sitting handcuffed inside a van. They don’t shy away from the camera.

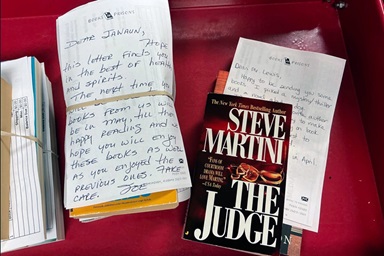

Coyotes who were caught smuggling people across the Rio Grande into the U.S. sit in the back of a Border Patrol paddy wagon near McAllen. After being searched for weapons and contraband, they placed their belongings, including their shoelaces, into plastic bags for safekeeping while their cases are adjudicated.

“We caught this guy two weeks ago,” remarks an agent, pointing at one of the men.

Lopez comments on how young the men are, but an agent disagrees. The agent says the men are 20, 21 and usually coyotes are “15 or 16 so they can’t get any charges filed against them. Both of these guys are from right across the border, Reynosa. We arrest them, feed them, they just go back.”

Rodriguez explains it is hard to prosecute someone under the age of 18 so the cartel usually uses young people.

A coyote who was caught smuggling people across the Rio Grande into the U.S. sits in the back of a Border Patrol paddy wagon near McAllen.

Rodriguez said there are more people in the field just across from the vehicles.

“The smugglers are quick to abandon the group. These folks have no idea where they are at, they are from a foreign country, they are following the guides and they (the guide) abandons them. In this case the guys abandoned them at the river and we caught them. It is not very often we catch them. The guide is the first one to take off.”

Soon the immigrants are rounded up and come trudging up the hill to the van. They are tired, dazed, their hair and clothes are full of thorns and debris from running through the thick fields. One young woman keeps trying to show the officers a piece of paper she has.

Rodriguez says it was her birth certificate. They often come with documents, he adds.

The Rev. Robert Lopez (left) learns firsthand about the work of the U.S. Border Patrol from agent Robert Rodriguez along the Rio Grande near McAllen. Lopez is superintendent of The United Methodist Church's El Valle and Coastal Bend Districts in the Rio Texas Conference.

The group is frisked, their shoelaces are taken as well as any other potential weapons such as knives, cigarette lighters.

“I guarantee they won’t say these are the guys who smuggled them. They are threatened before they come across,” Rodriguez says.

David Weeks, one of the agents, says he grew up here and never knew all this was going on.

“It’s a sad job. Most people just want a better life for themselves. My mother told me to just treat everybody right,” he says. “My mom says she would rather have me doing this job than just some jerk who doesn’t care out here with a badge and a gun."

Climbing back in the vehicle, Rodriquez says the agents in the northern ranchlands are making a concerted effort to find people quickly because of the extreme heat.

U.S. Border Patrol Agent David Weeks talks on the radio to direct a helicopter circling over a sugar cane field near McAllen, where people who had crossed into the United States illegally were hiding.

Read more, see photos

Catholic Charities volunteer Maria Peña (right) leads Honduran immigrants Isaác Rivera Ramos and his daughter Katerin to the bus station in McAllen, Texas.

View more photos from our trip to the U.S.-Mexico border on our Flickr page

Read the first story in the series: Faith communities provide respite, care for immigrants

Read related story: Native Americans pray at child detention center

“A lot of immigrants don’t come prepared to take a journey like that, the smugglers don’t tell them they need to hydrate because this is going to be a long journey — as a matter of fact they tell them the opposite, that it’s just a short walk,” he explains.

The agents try to discourage people from putting their lives in the hands of smugglers, he says. The port of entry is just a few feet from here, he points out, but the immigrants don’t know that.

“I had some people with me yesterday who said, ‘Why don’t these folks turn themselves at the port of entry?’ Everything is run by the cartel on the Mexican side so you can imagine sometimes they don’t offer them that option.”

The job of the agents is dangerous and emotionally draining. Often they recover dead bodies or people near death, people who have been kept in stash houses for extortion, or young girls who have been raped, he says.

A helicopter from U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Air and Marine Operations agency flies over a sugar cane field in a search for people who were trying to evade border patrol agents.

An agent from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service captures a man who had crossed into the U.S. illegally and had been hiding in a sugar cane field near McAllen. The wildlife officer, who is pointing to where other immigrants were hiding, had been helping border patrol agents search for a group who scattered into heavily wooded areas and nearby cane fields after they were spotted.

Rodriquez says the agency has a good relationship with the farmers in the area. Often people in the community come up and thank them when they see them in local stores.

“Of course, we have people on the opposite side, we had people protesting at our facility recently. As border patrol agents we are just doing what the government tells us to do, what the law tells us to do,” he says.

Lopez says there are mixed feelings in the church as well.

“We have agents who are members of our congregations. We also have people who have feelings for the people who are trying to cross,” he says. “It is important to listen, to build relationships, just to understand what you are going through.”

A U.S. Border Patrol agent escorts two young men who were caught entering the U.S. illegally.

Several times on the trip, Lopez talks about all the things happening in the place where he was born that he was not aware of. Rodriquez says he grew up in the area, too, but had no idea until he started working for the border patrol.

Further down the road, a group of four people are sitting on the side of the dusty road, wearing handcuffs, drinking water. They are being monitored by an agent.

Lopez sits down in the road to talk to a mother and her 16-year-old son.

After speaking to them for a few minutes, he gets up, dusts off his pants.

“They are just looking for the basics of life, this mother just wants a better life for her son,” the pastor says, explaining what the woman told him.

“You could sense they were at some kind of end to a long journey. She said she had been at it for a month. I asked if I could pray with her, I told her God was with her and she was quick to say, ‘I know God is with me.’ What else can you depend on but your faith? It’s a long and dangerous journey.”

“Our role in the church is providing safe spaces to have hard conversations. Demonizing people is just not helpful.”

The Rev. Robert Lopez (left) visits with a group from El Salvador and Guatemala who were caught entering the U.S. illegally by crossing the Rio Grande near McAllen. Lopez, superintendent of The United Methodist Church's El Valle and Coastal Bend Districts in the Rio Texas Conference, said the group had been traveling for a month to reach the U.S.

Gilbert is a multimedia reporter for United Methodist News Service. DuBose is a photographer for United Methodist News Service. Contact them at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.