If you think United Methodist disagreements today are intense, try the debate that Reformation leaders had about Holy Communion.

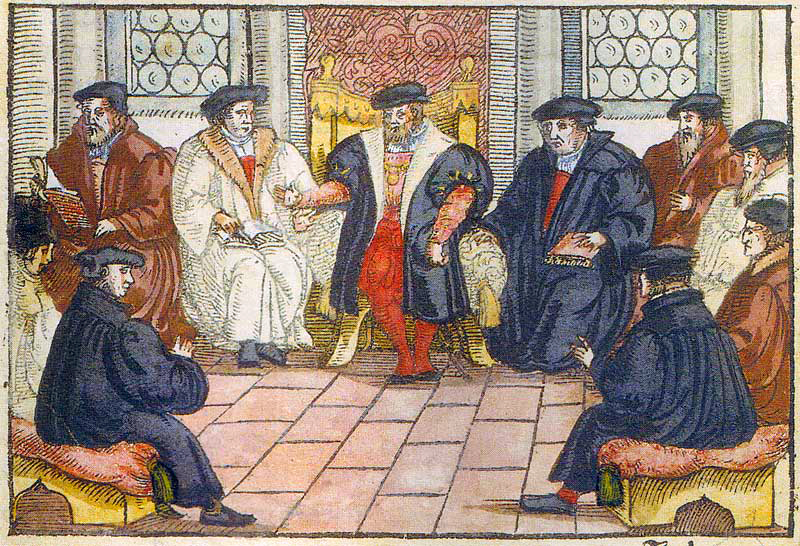

In 1529, a group of early Protestants leaders — foremost among them, Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli — met in Marburg, Germany to discuss theology. The goal was to form not just a religious alliance but also a political one in the face of mounting military challenges from Catholic authorities.

The Protestants agreed on 14 points of doctrine. However, things broke down over the Lord’s Supper.

Much of the clash hinged on different readings of the Bible. Even before the meeting, reformers had engaged in a war of words via rival pamphlets — the blogs of their day.

Luther argued that the Bible clearly quotes Jesus announcing his real presence in the meal. In the heat of debate, Luther reportedly took out a knife and carved into the table Jesus’s words: “This is my body.”

Zwingli contended that Christ’s presence in the holy meal was more spiritual than physical. Since Christ is “at the right hand of God,” Zwingli insisted, the savior couldn’t be at every altar. Zwingli and his allies also noted that the Bible clearly quotes Jesus speaking in metaphor calling himself “a vine” and “a door.”

The conflicting scriptural interpretations proved too much for the two men. Luther drove Zwingli to near tears. It was the Reformation’s first major internal split and left Protestants in no position to present a united front when trouble came.

More church splits resulted in some 45,000 Christian denominations worldwide, including The United Methodist Church, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity.

As United Methodists debate living together as one denomination, it’s worth noting where the reformers fell short. The splintering of the Reformation and the subsequent wars between Catholics and Protestants offer some cautionary lessons for how not to handle disagreements.

This year, Protestants — including United Methodists — will celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, which kicked off on Oct. 31, 1517 with Luther’s very public challenge to Catholic leadership over the sale of indulgences.

The move took guts. When Catholic authorities declared Luther heretical, the theologian refused to back down even though he put his life in very real peril.

“My conscience is captive to the Word of God,” Luther declared. “I cannot and I will not recant anything for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. God help me. Amen.”

World history would look very different without Luther’s defense of Christ’s justification by faith alone, his translation of the Bible into everyday German and his championing of the priesthood of all believers. Indeed, John Wesley himself at a critical point in his ministry took inspiration from Luther’s writing on Romans.

Perhaps no one was more surprised than Luther that some people would disagree with his reading of Scripture, said Anna M. Johnson, a professor of Reformation Church History at United Methodist Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary.

“His idea at least at the beginning is that by going back to Scripture, we’re going to agree because there is text with words that mean something,” Johnson said.

By invitation of the Landgrave Philipp of Hesse, Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli came to Marburg, Germany, in September of 1529. Some of their followers also attended. Anonymous woodcarving dating to 1557, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Click to enlarge.

The stakes were high for the reformers. Luther and Zwingli both came out of a late-medieval mindset of fearing God would go medieval on them if they did not get the faith just right.

“They are very focused on finding out what is orthodoxy and upholding that,” Johnson said. “There was even the belief that if they weren’t orthodox, God would wipe out their society because they were not being faithful.”

Nevertheless, historians agree, the failure at Marburg was a missed opportunity for reformers who shared more in common than not.

Zwingli, a Swiss reformer inspired by Luther and no less committed to the Bible, expressed deep disappointment in his former role model.

“You were that one Hercules who dealt with any trouble that arose anywhere,” Zwingli wrote in 1527 of Luther. “You would have cleansed the Augean stable, if you had had the images removed, if you had not taught that the body of Christ was supposed to be eaten in the bread.”

Luther, if anything, was even more reproachful.

“I wish from my heart Zwingli could be saved, but I fear the contrary; for Christ has said that those who deny him shall be damned,” Luther said upon learning of Zwingli’s death, according to the Table Talk recorded by his students.

Even shared emphasis on Scripture could not prevent the rift. The same certitude that led Luther to spread the Bible and empower lay people also led him to condemn Zwingli and late in life become viciously anti-Semitic.

Catholics were no less vehement in defending their own understanding of Christian orthodoxy.

Two years after the Colloquy of Marburg, Zwingli died in battle in a failed attempt to defend Zurich against Catholic forces. Luther died of natural causes in 1546, but less than a year later, his widow and children were forced to flee their home, as Catholic forces attacked Wittenberg, Germany.

Keep in mind, Christians were killing each other over doctrinal disputes — not least of all different understandings of the Eucharist.

Eventually this religious war ended with the Peace of Augsburg, which decreed the religious confession of the local ruler would determine the religious confessions of the people in his land. In theory, that meant a Lutheran would rule Lutherans, and a Catholic would rule Catholics.

Johnson said the peace agreement marked a significant milestone on the road to religious tolerance.

“Going into the Reformation, the assumption was that to have a united empire, everybody had to be of the same confession,” she said. “It’s a huge shift to say we can have parts of the empire that belong to different confessions and this will not undermine the empire as a whole. We don’t need to have uniformity to still have a cohesive society that functions.”

Sporadic bloodshed would continue. Catholics and Lutherans both could be especially brutal to Anabaptists, whom they viewed as too radical.

Nevertheless, Johnson said, neighbors of different confessions often did learn to live together in their communities despite strong religious differences.

“While the theologians are fighting tooth and nail and issuing pamphlets against each other, at the local level, it looks a lot different,” Johnson said. “People learned to negotiate difference.”

Hahn, who grew up in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.