As most good United Methodists know, John Wesley felt his heart “strangely warmed” as he listened to a reading of Martin Luther’s preface to the Epistle to the Romans.

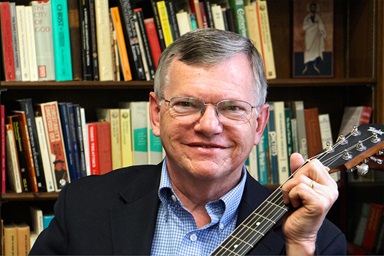

The Rev. Ted A. Campbell, associate professor of church history at Southern Methodist University’s Perkins School of Theology, gets a similar glow whenever he learns of a previously undiscovered letter by Wesley, who founded the Methodist movement in 18th century England.

Take the time Campbell heard that an administrator at Rice University owned such a letter.

“I just drove down to Houston giddy at the thought that this might be a real John Wesley letter that had never seen the light of day,” Campbell said.

Campbell did authenticate the letter. And the owner, Barbara Harrison, eventually gave it to Perkins’ Bridwell Library.

“I was delighted that he was so thrilled,” Harrison recalled. “That’s why I felt comfortable donating it. I knew how important it was to him.”

Transcription

[Letter mutilated. Address panel and left margin wanting]

Sept. 4, 1779 [D]ear Joseph

If there is ever a single man [ei]ther in the Nottingham or [Lei]cester Circuit, who will go [to] Canterbury in your stead let [hi]m set out without delay. It [is] all one to Your Affectionate Brother J Wesley [Wesley was in Bristol at this time, although he does not include the place in this letter. Richard Heitzenrater speculates that "Joseph" may been Joseph Pescod, who was in the Leicester circuit in 1777 and 1779 (in Pembroke in 1778), or perhaps Joseph Harper, who had been appointed to the Kent (Canterbury) circuit in 1778, the previous year (which had just ended).

The minutes also list in Kent for 1778 (along with James Rogers) a third person simply by initials, M. F. (for Michael Fenwick, who fell out of favor). I think Michael was a single rascal so perhaps Wesley was trying to replace him with another single man."]

There are plenty of John Wesley experts. But for this era, Campbell is the go-to scholar — “da man” as they say in sports — on Wesley’s letters.

He’s just finished editing the third volume of Wesley’s letters, covering 1756 to 1765, for the Wesley Works Editorial Project, a projected 34-volume, definitive collection of sermons, journals and letters. Campbell’s volume should be out next year from the United Methodist Publishing House.

Another three to four volumes will be needed to cover the balance of Wesley’s letters. Campbell, 60, will continue to balance teaching at Perkins with editing the letters, knowing the effort will likely consume the rest of his academic career.

“If I work to 70 or 75, I can do two to three more volumes,” he said.

Randy Maddox, a Duke Divinity School professor and current guiding force behind the Wesley Works Editorial Project, thinks Campbell is just the right scholar for this painstaking editing job.

“Ted brings high passion for this work — not just the passion to see it published, but for the details,” Maddox said.

On Wesley’s trail

Campbell grew up in a Methodist family in Beaumont, Texas, and attended Lon Morris College, a two-year United Methodist school in the East Texas town of Jacksonville. In the spring of 1974, he went with a group of fellow students to Perkins to hear Professor Albert Outler lecture on theology and the Wesleyan spirit.

“That was transformative,” Campbell said. “That was the moment I knew I wanted to pursue the Wesleyan studies thing.”

From Lon Morris, Campbell went to the University of North Texas, where he majored in Latin, reading John Wesley biographies in his spare time. He enrolled next at Oxford University in England – Wesley’s school. There, as part of Lincoln College, where Wesley was a fellow, he earned a bachelor’s in Christian theology. That’s the same degree Wesley had.

Campbell also served as a Methodist lay preacher during his two years in Oxford, and became friends with the Rev. Stuart Rhodes, a British Methodist clergyman who shared a story that seems in retrospect to have been an omen.

“Stuart told me that one day somebody had put two letters under the door of his study,” Campbell said. “They ended up being absolutely authentic letters John Wesley had written to a woman in Ireland.”

Black or red wax

Campbell returned to the United States, earning his Ph.D. at Southern Methodist University and becoming an ordained elder of The United Methodist Church. He’s since taught at Methodist Theological School in Ohio, Duke Divinity School, Wesley Theological Seminary and Perkins. He was president of Garrett-Evangelical Theological School from 2001 to 2005.

At Duke, his first regular full-time academic appointment, he got to work with Professor Frank Baker, who edited the first two volumes of John Wesley letters in the Wesley Works Editorial Project.

“He kind of took me as an understudy,” Campbell said.

For financial and other reasons, the project went on a long hiatus. Maddox got it going again in 2007, by which time Baker had died. At a breakfast meeting during an American Academy of Religion gathering, Maddox prevailed on Campbell to step up his work on the third volume of the letters.

Even though he’d been Baker’s protégé, Campbell didn’t quite know what he was getting into.

“It’s a tremendous learning curve,” he said.

Campbell had to ground himself in Wesley’s writing style, including abbreviations, as well as the vast cast of characters Wesley was writing to and mentioning in letters. Along the way he learned all about the postal service in 18th century England, which at points included thrice-a-day delivery in London.

“It was so good in London that sometimes you would send a note in the morning, it would be delivered that morning, the person receiving it would write a response, and it would be back that evening,” Campbell said. “It wasn’t quite email or text messages, but it was a very quick system.”

Campbell can now talk at length about the goose feather quills Wesley fashioned for writing and the kind of paper he used. He is pretty sure he can tell which letters Wesley wrote while riding in a carriage. He knows the minutiae of Wesley’s handling of letters, which were sent without envelopes.

“He would fold his letters in a very specific way that he always used, putting the address on the outside,” said Campbell, who has mastered the technique. “He’d put on his seal, either black wax or red wax, and he had a series of different seals. We can document his seals at different times of his career.”

A life in letters

Campbell believes Wesley’s letters yield a different perspective on the man than the sermons or journals.

Some letters offer Wesley’s views on theological matters and liturgical practices, and others elaborate controversies within the Methodist movement. Wesley’s tensions with his brother (and fellow Methodist movement leader) Charles Wesley are documented in the letters and by the absence of correspondence between them for long stretches.

Last year, Campbell published a scholarly article titled “John Wesley’s Intimate Disconnections, 1755-1764." It deals in part with John Wesley’s advisory letters to young women, including a warm one Wesley’s wife, Mary, intercepted, causing her deep hurt and straining their already difficult relationship.

“The letters reveal a very personal side of Wesley that is not present in his works that he wrote for the public,” Campbell said. “Some of it is very reassuring. Some of it is very pastoral, theological and profound. Some of it is problematic, like his relationships with these women that I have written about.”

Many of the letters are brisk and business-like, and the one Campbell drove to Houston to authenticate certainly meets that description.

“[D] ear Joseph If there is ever a single man [ei]ther in the Nottingham or [Lei]cester Circuit, who will go [to] Canterbury in your stead let [hi]m set out without delay. It [is] all one to Your Affectionate Brother J Wesley,” Wesley wrote a correspondent on Sept. 4, 1779.

That’s by no means the shortest.

“Some of John Wesley’s letters are like tweets,” Campbell said. “There’s one that says, ʽFrankie, why are you not in Bristol? Are you out of your wits?’ He doesn’t even sign it. It’s like, ʽDude!’ You can imagine him putting the little frowny face emoticon at the end.”

Attics and desk drawers

The contents of about 3,300 John Wesley letters are available to scholars. John Rylands Library in Manchester, England, has the most original manuscripts, with about 600; followed by Perkins’ Bridwell Library, with 135 (available online); and the United Methodist Archives Center at Drew University, with 130. Duke Divinity School has a massive collection of photocopies of letters and other Wesley material, assembled by Baker.

A while back, Campbell and a graduate student undertook a rigorous estimate, based on Wesley’s letter-writing patterns, and concluded he probably wrote about 18,000. Most are no doubt lost for good, but Campbell notes that previously unknown Wesley letters come up for sale every so often, with the going rate at about $3,000 to $4,000.

He suspects there are Wesley letters in the attics or desk drawers of people who don’t know how eager scholars are to see them.

Campbell is probably the most eager of all, though occasionally ambivalence takes hold.

“Sometimes I feel guilty because I know he never intended anyone else to see these letters,” he said.

The feeling always passes, or at least is overridden, by his scholar’s desire to understand Wesley as fully as possible.

So if you think you have a Wesley letter, Campbell welcomes hearing from you. And he will enjoy the irony of doing so by email, at [email protected].

Hodges, a United Methodist News Service writer, lives in Dallas. Contact him at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected]

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.