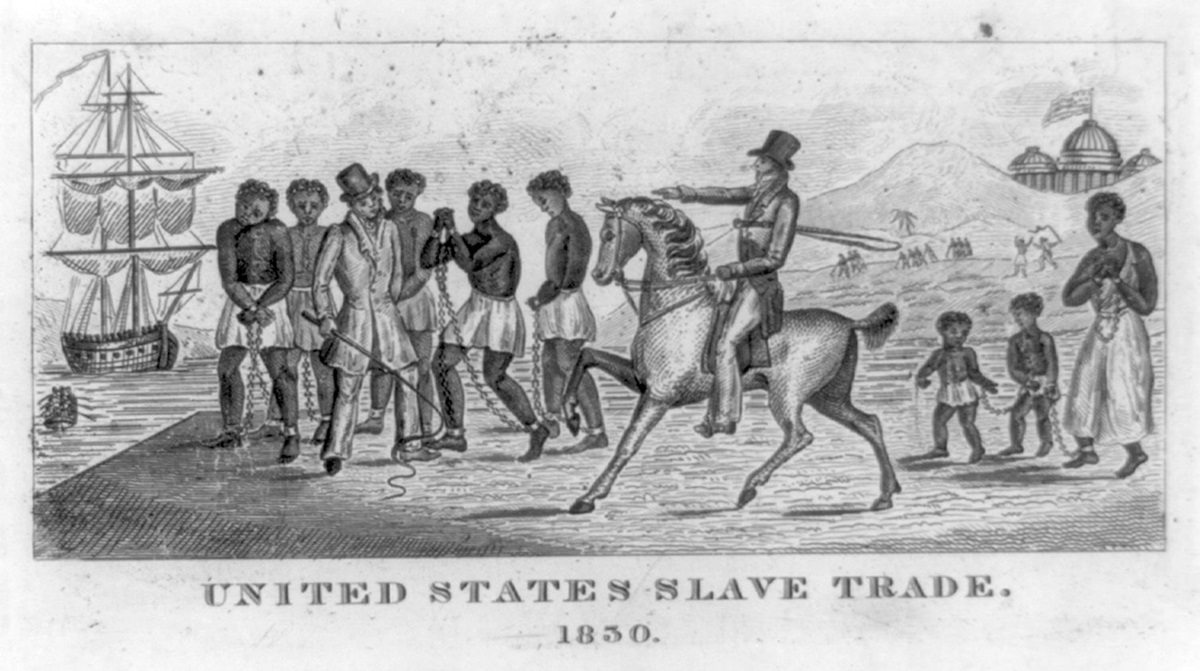

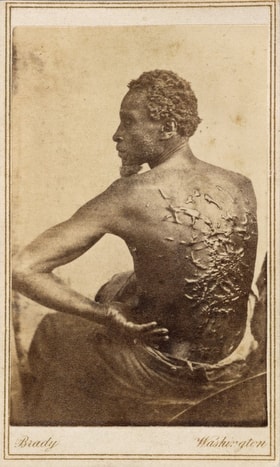

In August 1619, about 50 people from Angola arrived in Jamestown, Virginia — the first African slaves in what is now the U.S. Four hundred years later, African Americans still struggle with the onerous remains of that legacy.

“In 2019, after centuries of structural change, protests and policy reforms most often led by Africans and people of African descent, why do these groups still experience such disproportionately high percentages of hunger and poverty today?” wrote the Rev. Angelique Walker-Smith in the introduction to “Lament and Hope: A Pan-African Devotional Guide.” The guide, by United Methodist partner Bread for the World, was produced to help people reflect on the quad-centennial.

“And why is there still such a wide wealth and income gap between these groups and individuals of European and Asian descent?” she asked.

The devotional guide is among resources and events endorsed by three United Methodist agencies to help Christians study and commemorate the beginning of slavery in the U.S.

They include a prayer book, a commemoration of the 1619 landing at Fort Monroe Visitor and Education Center in Hampton, Virginia, and a United Nations initiative declaring the International Decade for People of African Descent.

It’s important to recognize it because we’re still living with the vestiges of what happened in 1619,” said Walker-Smith, senior associate for Pan-African and Orthodox Church Engagement at Bread for the World, a Christian non-profit that fights hunger. “We are still living with the lament and the hope that has come out from that period.”

John Wesley, founder of Methodism, referred to slavery as “that execrable villainy, which is the scandal of religion, of England and of human nature,” in a 1791 letter to William Wilberforce, a member of Parliament.

But white Methodists “had great difficulty in seeing a way to genuine equality,” said historian Alfred T. Day, leader of the United Methodist Commission on Archives and History.

“Methodism … has had a remarkable anti-slavery commitment but at the same time made troubling concessions to racism,” Day said. White Methodists dictated that Africans should always have the supervision of whites and not be permitted to meet by themselves.

“Black Methodists would embrace and treasure the Methodist egalitarian Gospel and the affirmation it offered, but quickly found their growth in the faith and the movement held back, stymied at most every turn.”

To this day, there are United Methodist pulpits where black clergy are unlikely to be appointed because of their skin color, according to Day. “We sort of tacitly accept that,” he said.

This year also marks a second important anniversary pertaining to U.S. race relations.

Fifty years ago in May 1969, James Forman, the head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, declared a “Black Manifesto.” The manifesto demanded $500 million in reparations be paid to African Americans by U.S. churches and synagogues for being “forced to live as colonized people inside of the United States, victimized by the most vicious, racist system in the world.”

Reparations were discussed June 19 in Washington during a congressional hearing on H.R. 40, a bill to create a commission that would propose ways to address the lingering effects of slavery.

The World Council of Churches released a statement May 27 calling for “all WCC member churches to find opportunities to commemorate this historic moment, to ask God’s forgiveness on behalf of our ancestors who were involved in the enslavement of African people and to recommit to the struggle against racism and for racial and economic justice and reparations.”

The Rev. Jean Hawxhurst, ecumenical staff officer for the United Methodist Council of Bishops, said that there would likely be opportunities this year “for some significant repentance for those of us who are privileged, but also conversations about reparations.”

The United Methodist Council of Bishops, Commission on Religion and Race and Board of Church and Society all contributed to “Stolen,” described as “a collection of resources and engagements to commemorate the quad-centennial of the first of the African diaspora brought to the American colonies.”

Among the suggestions are:

- “Lament and Hope,” the devotional guide from Bread for the World.

- “The Angela Project Presents 40 Days of Prayer: For the Liberation of American Descendants of Slavery,” a prayer book prepared by Simmons College in Louisville, Kentucky.

- The Angela Project Commemoration Ceremony at noon Aug. 20 at Simmons College in Louisville, Kentucky.

- “Arc of Freedom: Fort Monroe National Monument,” a video sharing a brief history of the first arrival of Africans to Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia.

- Commemoration of the 2019 landing, Aug. 23-25 at Fort Monroe Visitor and Education Center in Hampton, Virginia.

- International Decade for People of African Descent, an initiative launched by the United Nations recognizing that people of African descent are a community whose human rights must be promoted and protected.

- Christian Unity Days, Oct. 13-16 in Norfolk, Virginia, featuring field trips, discussions, fellowship and worship. The event is sponsored by the National Council of Churches.

Walker-Smith said everyone would benefit from racial reconciliation, not just African Americans.

“This is a cause for all of us. Once we really understand … the benefits when we’re able to call ourselves to reconciliation, … I believe we will receive the blessings of that.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.