Key points:

- Every Nation United Methodist Church in Anchorage was designed to support and minister to Alaska Natives.

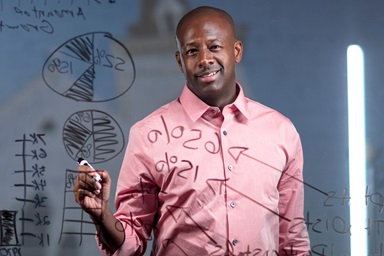

- The Rev. Murray Crookes, one of the only Alaska Native clergy in the state, hosts a weekly community dinner and Bible study as well as Sunday worship that incorporates Native traditions.

- Crookes also started a nonprofit that aims to provide a safety net for struggling Native people who might otherwise fall into a desperate situation.

When the Rev. Murray Crookes returned to his home state of Alaska in 2018 to start a new church, he wasn’t sure where to begin. He spent a lot of time in the community before learning of a regular gathering of Alaska Native people meeting at a local Days Inn.

“I saw people singing in Yup’ik and invited them to come have a meal with me,” he said. “We started with a meal, then a Bible study, then we would sing. It was important to find ways to worship in the most genuine way possible.”

Nina Gorman, who met Crookes at the hotel gathering, said she then started recruiting others “because people need to be spiritually fed to succeed.”

The new congregation, Every Nation United Methodist Church, began meeting on Tuesdays because many other churches offer meals on Wednesdays, and Crookes wanted people to be able to get a meal on a night that they might not be able to otherwise.

Crookes, who had served at churches in the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference prior to returning to Alaska, said that this food ministry was different than any other in which he participated.

“Before, the focus was on feeding people and the other stuff was extra, but people here get excited about the Bible study. It’s what really draws people and they invite their friends to be a part,” he said.

There was also Sunday worship, which Crookes describes as being “a standard-issue United Methodist liturgical service.” He soon realized that though he’d consider it a good day if six or seven attended Sunday worship, the church was feeding 50 on a Tuesday night.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Crookes discovered what he calls his “accidental ministry.” Since people couldn’t come to the meal in person, he would make meals to go and deliver them all over town.

“That’s been a regular thing ever since, just showing up and being a connection to the world. Back then it was vitally important and it’s still important today,” he said.

Gorman said Crookes was “a lifesaver” during that time.

“Many times, when I wasn’t home, Murray would just hang food on my door, and brought me food and medicine when I was sick,” she said, adding that the online worship services during lockdowns kept the congregation together and “kept our faith strong.”

The Rev. Christina DowlingSoka, superintendent for the Alaska Conference, said Crookes’ great strength is listening.

“It’s great to have him in a community model of visiting with people and empowering them to make a difference,” she said.

When the congregation could meet in person again, Crookes overhauled the Sunday worship service completely. Worshippers began meeting at 2 p.m. and instead of the traditional altar-and-pews setup, they started sitting in the round.

Everything has a more informal feel to it now, which he said has enhanced the worship experience.

“I encourage them to get coffee, sit down and be comfy. People will interrupt me while I’m preaching to ask questions, and I love that,” he said.

Gorman praises Crookes for being “down-to-earth and nonjudgmental.”

“This is a healthy community gathering where people don’t have to come dressed up — just show up as you are,” she said.

Children are also involved in the service. Blankets are placed on the floor, just outside the circle, with coloring books and other activities, and Crookes does a short devotional for them.

“We don’t leave children out of any part of the life of the church,” said Crookes’ wife, Maria, who is a United Methodist deaconess. “If we move them away from the Lord’s teaching, then what are they here for?”

Crookes has introduced Native elements into the service, some of which he picked up while in Oklahoma or from other parts of Alaska. He does a smudge — a cleansing ritual involving burning sage — before Sunday service and offers to smudge anyone who’d like it. There is a shell and eagle feather placed next to the Christ candle on the altar. He also sings a Kiowa hymn after reading Scripture and encourages others to sing a song in their Native language.

“One of my dreams is that it will become a practice here where we can share and sing each other’s songs and celebrate them regularly,” he said. “I love when worship is more than just coming to worship God; it’s a celebration of culture and language.”

Every Nation’s emphasis as a Native faith expression was the vision of the Greater Northwest Episcopal Area’s Innovation Vitality Team and Circle of Indigenous Ministries. The church is designed to support Alaska Natives while also being a multicultural gathering space. It is now the second-largest Alaska Native worshipping community in the state, and among the largest indigenous worshipping communities in the Greater Northwest Area.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“Indigenous ministries can’t be treated like other ministries. It’s a very different thing,” said Greater Northwest Area Bishop Cedrick D. Bridgeforth.

Kristina Gonzalez, executive director of the Innovation Vitality Team, said Crookes’ Alaska Native heritage and passion for gathering Native people together made him “the perfect fit for the calling of developing community with the traditionally underrepresented.”

Crookes said that his heritage seems more noticeable and meaningful to others at Every Nation than in other places he has served.

“People recognize me as a Native man, who my family is and where they’re from,” he said. “Here, there’s a lot of folks familiar with my family name, so people might come to see this pastor in town related to people they know.”

The familiarity with his family name comes from the fact that Crookes’ great-grandfather was the last medicine man in his village.

“There are people alive today who were healed by him so there’s a certain degree of mysticism around his name and spiritual leaders who carry that name.”

Crookes has been approved for ordination when the Pacific Northwest Annual Conference meets in June, which will make him only the third Alaska Native clergy currently serving in the state, and one of just a few in the entire U.S.

The Tuesday dinner is a family affair, with both Murray and Maria preparing food and their two daughters helping to set tables. Just like the worship service, the Bible study after the meal is informal and Crookes invites others to join the discussion.

“I like that Murray allows us to make comments, includes everyone listening,” said Annie Kuku Stewart, who has been coming to the Bible study for about a year.

Crookes said that he offers the meal first for those who don’t want to stay for the Bible study, but few wind up leaving after they eat.

“Once, I said let’s just have a meal, sing songs and go home, and someone said, ‘We’re not going to do the Bible study? That’s why I came!’

“That tickled me,” he said.

For the past year, Crookes has been developing a nonprofit called the Alaska Native HOPE Network, with HOPE standing for History of Oppression, Project of Empowerment. The goal is to partner with other community organizations to create a safety net of resources for Native people who may be struggling.

The state is populated with small, rural villages of mostly Native residents, and they usually have to come to Anchorage for work, medical needs or school.

“Life in the big city is vastly different than life in the villages — particularly for Alaska Natives,” Crookes said, and those who find themselves without the means to return to their village wind up stranded in Anchorage with no support system.

“We want to create trust with people who come here from the villages,” he said. “When they don’t know who to turn to, they can be directed to us so they don’t have to go into the street, fall into a desperate situation or self-harm.”

Crookes wants not only to help the community but also to challenge stereotypes others may have about Alaska Natives.

“We are more than statistics paint us and we can change that narrative. It just takes time,” he said. “If there’s more Alaska Native men who learn their heritage and culture is valuable and meaningful, they might not fall into narratives of hopelessness.”

Acknowledging that he’s “a seminary-trained pastor,” Crookes said the administrative aspects of nonprofit and social justice work may not be his expertise, but that’s where his heart is.

“It’s like when I got my Master of Divinity degree. I said that what I’m studying, the thing I’m passionate about; it’s hardly work at all.”

Butler is a multimedia producer/editor for United Methodist News. Contact him at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected]. DuBose is a freelance photographer in Nashville, Tennessee. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.