부활절 직전 그레고리 닐 목사는 교인들에게 빵 조각이나 핫도그 빵 그리고 약간의 주스나 와인으로 가정 제단을 만들라고 권면하는 이메일을 보냈다.

부활절 당일, 닐 목사는 카메라 앞에 서서 텍사스주의 파머스빌 제일연합감리교회 온라인 예배를 통하여 성만찬을 집례했다. 그는 코로나19 때문에 대면예배를 드릴 수 없는 상황에서, 온라인 성만찬을 집례할 수 있게 된 것을 기뻐했다.

닐 목사는 “우리 각자가 작은 공간에 격리되어 친교를 할 수 없는 지금이 예수의 은혜가 그 어느 때보다 더 필요한 때다.”라고 말했다.

캘리포니아주의 출라비스타에 위치한 제일연합감리교회의 브라인언 파셀 목사는 코로나19 격리 기간에 성만찬을 집례하지 않기로 결정했다. 그는 성경과 연합감리교 교리의 지침대로 목회자와 회중이 직접 참여해야만 성만찬이 가능하다고 믿는다.

파셀 목사의 교회는 보통 매 주일 주일예배 3번 중 2번의 예배에서 성만찬을 한다. 파셀 목사는 “성만찬이 우리 존재의 중심”이지만, 대면예배가 재개될 때까지 <성만찬금식>을 하고 있다고 말했다.

"사람들은 그들이 잃어버린 것이 무엇인지 깨닫게 될 것이기 때문에, 이 (성만찬금식) 시간은 매우 성스러우면서도 엄숙한 순간이 될 것이다."라고 그는 말했다.

코로나19 대유행으로 인해, 대면예배 중단으로 인해 성만찬을 갖지 못 하는 상황에서 연합감리교회 교단 내에서는 온라인 성만찬이 가능한지 여부를 두고 여러 측면에서 논쟁이 벌어졌다.

감독들은 온라인 성만찬에 관해 각자 다른 입장을 밝혔고, 예배학 학자들은 자신들의 충고에 귀 기울여야 한다고 주장했고, 목회자들는 자신과 회중에게 합당한 것이 무엇인지 결정해야 했다.

웹사이트, 블로그, 팟캐스트 그리고 소셜 미디어 등에는 온라인 성만찬에 대한 찬반 논쟁이 차고 넘쳤다.

공통된 목소리가 있다면, 그것은 최근 수십 년 동안 연합감리교회에서는 성만찬이 (일반적으로 한 달에 한 번씩 행하는 것보다) 더 자주 행해지고 있으며, 목회자나 평신도가 성만찬을 전보다 더 중요하게 인식하고 있다는 것이다.

퍼킨스 신학교의 기독교 예배학 교수이자 코로나19와 온라인 성만찬에 관한 논문의 저자인 마크 스탐 목사는 "그 사실이 현 상황을 더 어렵게 하는 것 중 하나다.”라고 말하면서, “하지만 이에 관한 토론을 하는 것은 좋은 일이다."라고 덧붙였다.

연합감리교회가 인정하는 성례전은 2가지인데, 주님의 만찬, 혹은 성찬식으로 알려진 성만찬과 세례이다.

새로운 형태의 성만찬의 시도는 감리교에게 있어서 새로운 일은 아니다.

1938 년 5월 24일, 가필드 옥스남 감독은 전국적으로 매스컴을 탔다. 그는 1,500곳의 중서부 지역 교회에 모인 50,000여 명의 교인에게 라디오 방송을 통해 성만찬 예문을 읽어주고, 그 다음 목회자가 교인들에게 성만찬을 분급하도록 했다. 당시 많은 목회자들이 안수를 받지 않았기 때문에, 감독의 도움 없이는 성만찬을 집례할 수 없었다. (편집자 주: 현 연합감리교회에는 안수를 받지 않았으나 자신이 섬기는 교회에 한해서 성만찬과 세례를 행하도록 라이센스를 발급받은 평신도 목회자인 본처 목사 제도가 있다.)

연합감리교의 성만찬에 대한 이해는 2004년 총회에서 채택된 “거룩한 신비(This Holy Mystery)”라는 제목의 문서에 고스란히 담겨 있으며, 이 문서는 성례전을 행하기 위해서는 교인들의 실질적 참여가 중요하다고 강조하고 있다.

캔들러 신학교의 예배 및 전례학 부교수인 에드 필립스 목사는 2004년 당시에도 인터넷은 잘 사용되었지만, 그의 글은 온라인 성만찬의 가능성을 고려하지 않고 작성된 것이라고 전했다. 그는 연합감리교회 성만찬 문서인 “거룩한 신비”를 작성한 연구팀의 위원장이었다.

당시에도 많은 교회가 인터넷을 사용하여 녹화 또는 생중계로 예배를 진행하는 상황에서, 필립스 목사는 온라인 성만찬에 관한 연합감리교회 연구팀을 2013년까지 이끌었다. 학술적 논문 교환과 상당한 토론을 거친 후, 이 연구팀은 온라인 성만찬에 대해 일시 정지를 권고했고, 총감독회도 이를 지지했다.

2020년 3월로 빠르게 거슬러 오면, 미국과 전 세계의 수많은 지역에서 코로나19의 확산으로 교회를 포함한 공공장소가 전례 없이 문을 닫게 되었다.

몇 주 사이에 수천의 연합감리교회가 온라인 예배를 시작하거나 기존의 온라인 예배를 강화했다. 교회가 성만찬을 갖게 될 성목요일과 부활절을 앞둔 고난주간에는 많은 교회가 인터넷으로 몰려들었다.

감독들은 뜻밖에 온라인 성만찬을 인정할 것인가에 관한 문제에 직면했다.

존 숄 감독이 대뉴저지 연회가 진행한 줌 온라인 성만찬 예배에서 성만찬을 주재하고 있다. 사진, 대뉴저지 연회의 줌 성만찬 예배 장면 캡처.

존 숄 감독이 대뉴저지 연회가 진행한 줌 온라인 성만찬 예배에서 성만찬을 주재하고 있다. 사진, 대뉴저지 연회의 줌 성만찬 예배 장면 캡처.미국 내 코로나19 위기를 가장 먼저 접한 서부지역 총회의 다섯 감독은 자택대피령이 해제될 때까지 온라인 성만찬을 허용한다는 서한을 3월 24일 발표했다.

감독들은 편지에서, “우리는 이 사회적 거리두기의 시기에 모든 교회가 성만찬을 행해야 한다고 주장하지는 않는다.”라고 말하고, "그러나 우리는 성찰과 기도를 통해, 이 시기에 (온라인을 통한) 성만찬을 나눔을 통해 우리 회중이 강건함을 유지할 것이라고 믿는 목사들의 입장을 지지한다.”라고 밝혔다.

서오하이오 연회의 그레고리 팔머 감독과 그의 감리사회는 16세기의 흑사병 이후, 심각한 비상사태가 기독교적 관습의 변화를 초래했다는 내용의 논문을 공동으로 작성했다. 다른 연회의 감독들은 온라인 성만찬을 허용하기로 한 서오하이오 연회의 논문을 인용했다.

연합감리교뉴스의 확인 결과, 미국 내 대다수 감독과 아프리카, 유럽 및 필리핀의 일부 감독들은 코로나19 관련 제한이 시행되는 동안 온라인 성만찬을 허용했다.

서스퀘하나 연회의 박정찬 감독은 처음에는 자신의 연회에 속한 목회자들에게 온라인 성만찬을 하지 말라고 권고했다. 하지만 그는 자신의 감리사회와 더 많이 기도하고, 상황에 대한 성찰를 거친 후 입장을 선회했다.

박 감독은 존 웨슬리를 인용했다.

“웨슬리는 당시 영국 공교회의 일반적인 관행을 벗어나 하나님의 은총을 받는 방법을 사람들에게 제공했다. 이것이 우리가 할 수 있는 방법의 하나다."

또 다른 감독들은 목회자들에게 온라인 성만찬을 실시하지 말라고 권고하거나 지시했다. 특히 대신에 예수가 제자들과 나눈 식사를 회상하는 애찬식과 같은 기독교인들의 친교 방법을 대안으로 제시하기도 했다.

텍사스 연회의 스콧 존스 감독이 그중 한 사람이다.

그는 "그리스도인들은 과거에도 이와 같은 전염병을 경험했다. 그 당시 우리는 성만찬을 중단했다."라고 말했다.

서펜실베니아 연회의 신시아 무어-코이코이 감독은 자신이 온라인 성만찬을 승인하지 않기로 한 까닭은 지금이 비상사태 기간이기 때문이라고 했다.

"나의 심리학적 경험에 비추어 보면, 사람들은 스트레스를 받을 때 최선의 결정을 내리지 못 한다. 따라서 지금은 우리가 성만찬에 관한 신학적 관점을 바꾸기 위한 최선의 시기가 아닐 수 있다."

존스 감독과 무어-코이코이 감독은 다른 동료 감독들의 결정을 판단하지 않았다.

“우리 모두 우리가 할 수 있는 최선을 다하고 있다. 아무도 이런 위기에 어떻게 감독의 역할을 수행해야 하는지 가르쳐주지 않았다."

중부텍사스 연회의 마이크 로우리 감독은 자신이 유나이티드 신학교의 저스터스 헌터가 쓴 논평을 포함한 독서와 심사숙고 끝에 자신의 생각을 재정리했다고 언급하며, 온라인 성만찬에 대한 지지를 철회했다.

로우리 감독은 자신과 다른 감독들의 책임을 통감했다.

“나의 개인적인 결정이나 다른 감독들의 판단을 곰곰이 생각해보면, 감독 개개인 혹은 전체로서 우리가 이 문제를 다루어 온 방식에서 연합감리교회의 신학적 빈곤이 드러났다.”라고 로우리 감독은 전했다.

한편, 성례전에 관한 전문가들을 포함한 연합감리교 예배학 학자들도 이번 논쟁의 한 부분을 담당했다.

지난달 감독들에게 보낸 편지에 13명의 학자가 서명했다. 보스톤대학 신학교의 예배학 교수 캐렌 터커 목사와 함께 필립스 목사가 이 일에 일조했다.

“이 편지의 목적은 일부 감독들에 의해 허용되거나 심지어 장려된 온라인 성만찬에 대한 교리학적, 신학적, 목회적 그리고 다른 교단과의 관계에 미칠 영향에 대한 우려를 표명하기 위한 것이었다.”라고 터커 목사는 말했다.

웨슬리 신학교의 교회사 부교수인 라이언 댄커는 볼티모어-워싱턴 연회의 웹사이트에 게시된 자신의 논문을 이용해 온라인 성만찬에 반대한다고 밝혔다.

댄커는 연합감리교인들에게 있어서 온라인 성만찬은 “성례전적인 입장에서는 불가능한” 일이라고 주장했다.

“연합감리교의 교리와 예문에 따르면, 안수를 받은 목사 또는 본처 목사(라이센스를 받은 평신도 목회자)가 교인들이 모인 공동체에서 집례할 때, 진정한 그리스도의 임재가 떡과 포도주에 임한다고 믿는다. 모든 문장이 성만찬을 위해 필수적이다."

북텍사스 연회의 교회개발국 디렉터인 오웬 로스 목사는 “온라인 성만찬이 필요한 10가지 이유”라는 제목의 자신의 글에서 그 주장을 반박했다. 무엇보다도 로스는 온라인 성만찬이 교회에 갈 수 없는 사람들에게 영적 “만나”를 제공해줄 수 있다고 주장한다.

개체 교회 차원에서도 만장일치의 지지를 얻은 의견은 없다.

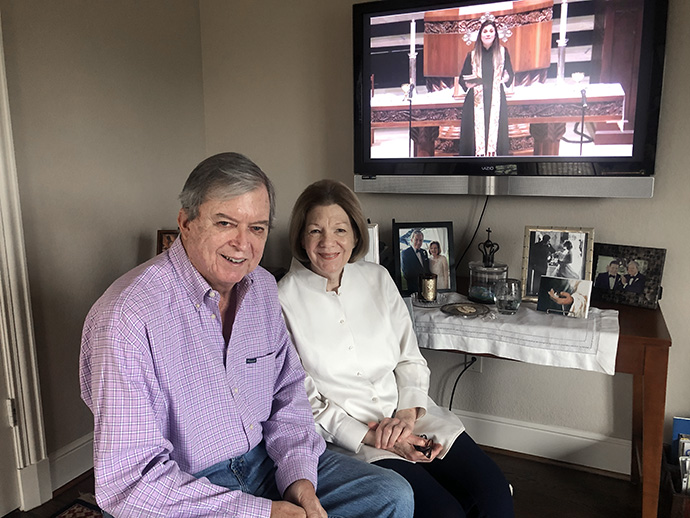

렉스와 샌디 호베 부부가 자택대피 중 달라스 하이랜드파크 연합감리교회의 온라인 성만찬 예배에 참여하고 있다. 사진 제공, 렉스 조베.

렉스와 샌디 호베 부부가 자택대피 중 달라스 하이랜드파크 연합감리교회의 온라인 성만찬 예배에 참여하고 있다. 사진 제공, 렉스 조베.

달라스 하이랜드파크 연합감리교회 교인인 샌디 호베는 “그리스도와 그분이 우리의 삶에 행하신 일을 기억하는 것은 우리에게 매우 특별한 일이다.”라고 소감을 밝혔다.

아이오와주 브루클린에 위치한 그레이스 연합감리교회의 조이스 프록터 목사는 부활절 예배에서 온라인 성만찬을 인도했음에도 불구하고, 교인 개개인의 이름을 부르며 성만찬을 분급했던 때를 그리워했다.

“그날의 온라인 성만찬은 외로운 성만찬이었다.”라고 그녀는 말했다.

조지아주의 수가힐에 위치한 수가힐 연합감리교회의 제프 콜맨 목사는 매우 활발하게 성만찬을 교인들에게 베풀며 교회를 이끌었다. 이 비상사태가 발생하자, 콜맨 목사와 교역자들은 북조지아 연회에서 배포한 사례집을 검토한 후 온라인 성만찬을 실시하기로 결정했다.

“우리는 우리 의견에 동의하지 않는 친구들과 동료들이 있다는 사실을 알고 있으며, 신학적으로 성만찬을 다루는데 있어서 민감하려고 노력했다.”라고 콜맨 목사는 말했다.

캔들러 신학교 교수인 필립스 목사는 지금은 앞으로 나아가야 할 시간이라고 말한다. 그는 의료 전문가와 다양한 교회 지도자들이 참여하는 안전한 성만찬을 위한 절차를 개발하기 위해 단기 프로젝트를 진행하고 있다.

그는 차후 모임을 통해, 연합감리교회의 온라인 성만찬의 미래를 다루기를 원한다.

"나는 선한 믿음으로 사역하는 평신도와 목회자를 골치 아프게 하고 싶지 않다. 위기의 시간에서 조금 벗어난 후, 이것이 좋은 일이었는지 그때 이 일에 대해 생각해보고 결정하도록 하자."라고 그는 말했다.

샘 하지즈는 달라스에 근거를 둔 연합감리교뉴스의 기자다. 연합감리교회 뉴스에 연락 또는 문의를 원하시면 김응선 목사에게 [email protected]로 하시기 바랍니다.